The 1935 International Marimba Symphony Orchestra

A HIGHLY SUCCESSFUL FAILURE

David Harvey

In May 1935, King George V of England celebrated his Sliver Jubilee, marking 25 years on the throne. Massive celebrations took place in London preceding that event, to herald this milestone in British public life. Clair Musser seized this moment to form a 100 piece marimba orchestra for the purpose of traveling to England to perform on this auspicious occasion, as this represented an opportunity for worldwide recognition of the marimba. Because the itinerary was international, the name of the ensemble was the International Marimba Symphony Orchestra. Musser was Director, Conductor, and Arranger of this massive ensemble. [Photos 1, 2, & 3]

At that time, Musser was head of the mallet instrument division of the Deagan company, and therefore he and Deagan management agreed to manufacture 102 marimbas in a limited edition production run. 100 of these special issue instruments were for the 100 members of the orchestra; one instrument was for use as spare parts; and the final marimba was for Musser's personal use.

Photo 4

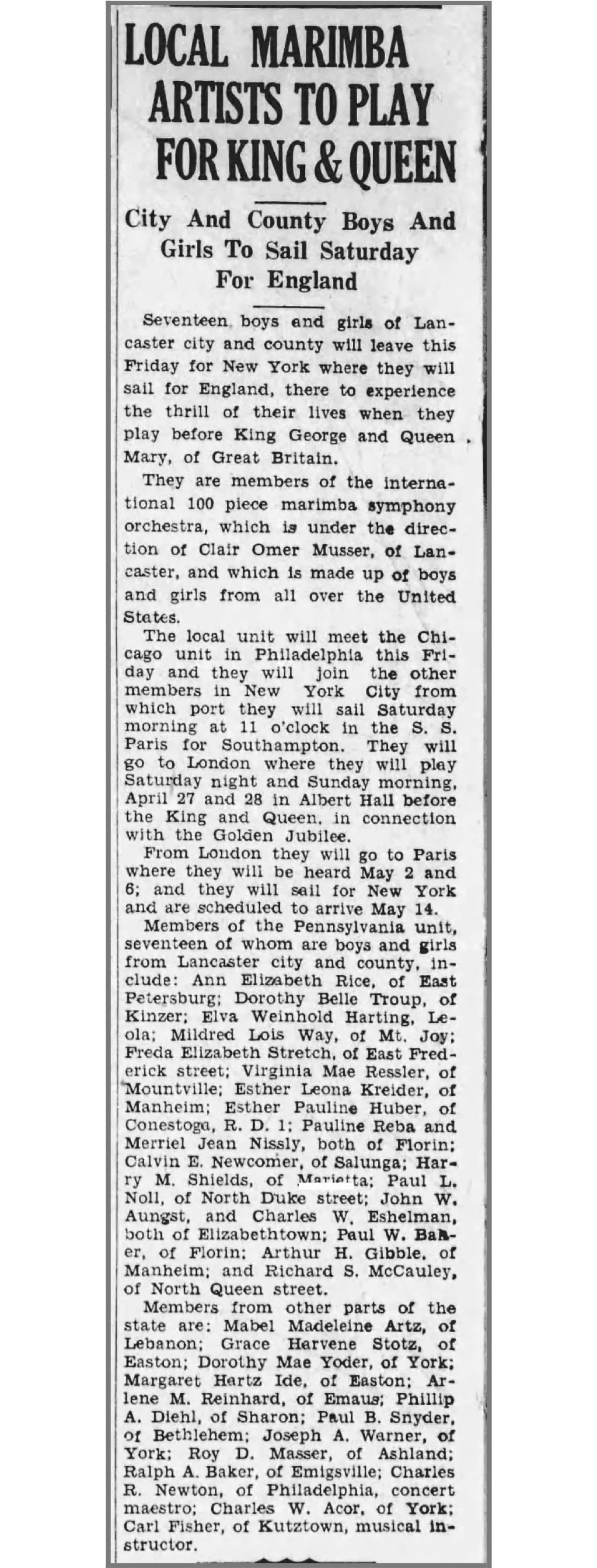

Participating musicians were drawn from across the United States. [Photo 4] Musser wanted to have the orchestra consist of 50 young men and 50 young women, but the breakdown ended up being 48 men and 52 women. The most members from a single region were from Pennsylvania, which contributed thirty-three members. This may have been due to the fact that Musser was from Pennsylvania, and had contacts there. Seventeen members of the Pennsylvania contingent were from eastern Pennsylvania. [Photo 5] Marimbist Carl Fisher of Kutztown Pennsylvania was the assistant conductor of the orchestra, and manager of sectional rehearsals for this eastern Pennsylvania group. They rehearsed in the local Farmers Supply store in Lancaster Pennsylvania. [Photo 6] The greater Chicago area sent twenty-six members, who rehearsed at the Deagan factory in Chicago. [Photos 7 & 8]

Although much can be said about this historic venture, there occurred in particular a rather remarkable series of failures encountered by Musser's IMSO, leading ultimately to a triumphant conclusion.

Photo 6

Photo 7

Photo 8

Photo 5

In April 1935, in preparation for the groups international tour, about two thirds of the orchestra assembled at the Greenbriar Hotel in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. There, they rehearsed, and performed a series of concerts, one of which was broadcast over CBS radio. [Photos 9 & 10] Following this residency, the musicians went to New York, where they assembled with the remaining orchestra members. The ensemble boarded the French luxury liner S.S. Paris, and embarked for the port of Southampton England. [Photo 11] While traveling, the marimba orchestra performed for ship’s guests in the opulent Grand Salon. [Photos 12 & 13] Misfortune then struck, as one of the young men of the orchestra died due to a health situation. [Photo14] The result was that before the IMSO had reached its first tour destination, it was no longer a 100 piece ensemble, as had been promoted. This tragedy was, unfortunately, only the first setback to befall the International Marimba Symphony Orchestra.

Nevertheless, the ship arrived in England as planned, for its two Silver Jubilee musical performances scheduled in London's Royal Albert Hall. Upon arrival, however, a drama unfolded that was rooted in prior events originally having nothing to do with the IMSO. A highly popular British dance band had recently traveled to New York City to perform, but was cancelled due to a dispute involving the musicians union there. This decision was bad international diplomacy, which set the stage for an unfortunate reprisal from the English government towards the United States.

This political response came in the form of a British government official, who upon greeting the marimba ensemble at the dock informed them that the IMSO would not be allowed to perform in the Silver Jubilee celebration concerts as anticipated. [Photo 15] This decision was simply a measured rejoinder to repay the Americans for their earlier poor treatment of the British dance band in New York. The orchestra members did not even disembark the ship in the English port. What a horrible setback this must have been to endure for the musicians and their conductor, who had worked so hard for many months in preparation for this international gala.

Photo 15

The unique King George marimbas had been designed specifically for the King George V celebrations, including a coat of arms plaque on the front of each instrument, which is a British stylistic feature. However, these marimbas were not presented at the King George celebration as planned, and ultimately the British public who attended those events never even knew of their existence. Ironically, the Deagan King George marimbas could today more aptly be called the "Almost King George" marimbas, as they never actually were used for their intended namesake involving King George V. This almost unbelievable turn of events was yet another setback to befall the International Marimba Symphony Orchestra, denying the organization the very basis for its formation.

Photo 16

Fortunately, the IMSO itinerary included a European tour following their London engagement, to then conclude with a Carnegie Hall performance in New York upon their return to the US. The orchestra therefore left England and continued on, travelling to Paris and then to Brussels, returning again to Paris, for a series of concerts for the European concert going public. It was at the first of these concerts at the Salle Rameau in Paris that the next very serious problem cropped up: the 100 marimbas of the IMSO would not fit on the stage! Therefore, Musser abruptly selected a reduced member contingent for this performance. [Photo 16]

As it turned out, this layout difficulty plagued the orchestra everywhere it went. In fact, due to this ongoing logistics challenge, the 100 members of the International Marimba Symphony Orchestra did not once publicly perform together as planned. In light of this astonishing fact, this legendary 100 piece marimba orchestra existed as a 100 piece orchestra on paper only! This was yet another traumatic failure endured by the IMSO.

It should be noted that two years prior to the IMSO tour, Musser had created another 100-member marimba ensemble, the Century of Progress Marimba Orchestra, which did in fact perform in Chicago together in its entirety. However, the venue for those performances was outdoors in the court of the Science Pavilion at the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition. That open-air spaciousness accommodated the 100 marimbas and their performers easily, unlike the confines of an indoor concert hall stage.

Apparently, Musser learned from this bitter IMSO experience, as after the 1935 tour he scheduled other subsequent marimba orchestras many times, but usually at an outdoor venue in Chicago; Soldiers Field. At these outings, many outdoor bleachers and risers were arranged to accommodate the massive assemblage of marimbas as needed, at times numbering up to 300 marimbas. Musser also conducted stage performances with considerably smaller marimba ensembles, which typically consisted of members extracted from the full-sized outdoors groups.

On the bright side, the orchestra's European performances went very well musically, and were received publicly and critically with vigorous enthusiasm and acclaim. These European concerts were publicized throughout the regions where the IMSO appeared, lending public focus on this project. [Photos 17, 18, & 19] The front page of the Excelsior, a leading Parisian newspaper, announced the upcoming Paris IMSO concert, with the caption:

“100 performers of a new instrument called marimba are presented this evening in Paris for the first time in Europe. It is the most perfected percussion instrument that has been produced to date. On a very wide musical scale, it allows the attainment of effects of a novelty and astonishing richness. This orchestra was the great attraction of the Chicago Exhibition in 1932, where it won the first Grand Prix.”

In Brussels, a critic for the Le Soir newspaper was thoroughly impressed:

“The Marimbas used by the International Marimba Symphony Orchestra are improved to such a degree that they give an ideal sound which is essentially modern. We had expected terrific sounds, something that would have broken our ears; we thought of witnessing one hundred Siegfrieds hammering multiphonic anvils with all their might ... nothing like this happened.

The tones were soft and even veiled. The far away sounds seem like those of an Aeolian Harp. It is as if each note from a bell lolls on the vaporous harmonic tissue like a drop of gold. The energy of percussion does not give harsh sounds, and all these musicians are technicians of the first water, with a profound sensitiveness.”

Things went so successfully that the orchestra received an invitation to expand its European tour to more than a dozen other cities, but Musser declined due to previously scheduled travel commitments.

Photo 20

What happened next in this tour, however, bordered on the surreal. The IMSO became stranded in Paris, due to a total depletion of funds. It should be noted that the 100 marimbas were each packed into two trunks, for a total of 200 trunks weighing an aggregate of approximately 25 tons. A photo of all the trunks had been taken at the Chicago Deagan building, showing just how massive this freight was. [Photo 20] The cost of constantly moving this extraordinary conglomerate of parcels across Europe undoubtedly contributed to a sharp increase in expenses unforeseen in the planning stage of this expedition. To make matters worse, French authorities impounded the marimbas as collateral for monies due! Bereft of funds, the orchestra members were thus reduced to prisoners under house arrest, unable to travel, perform, pursue their itinerary as scheduled, or return home.

As the International Marimba Symphony Orchestra was a Deagan organized project, Clair Musser appealed to Ella Deagan, who was then President of J. C. Deagan, Inc. for financial assistance. [Photo 21] The amount of money needed to bail out the orchestra's marimbas and cover further travel and accommodations for the musicians was $10,000. Without hesitation, Ella Deagan wired $10,000 USD to Musser to bail the group out. To put this expense in perspective, $10,000 dollars in 1935 is approximately equivalent to $202,000 dollars today. Can you imagine if an American marimba company today sponsored a marimba orchestra to tour Europe, and suddenly received word from abroad that an additional $202K was needed immediately? This fourth massive catastrophe experienced by Musser's marimba ensemble in 1935 capped a series of challenges that defied expectation.

Photo 21

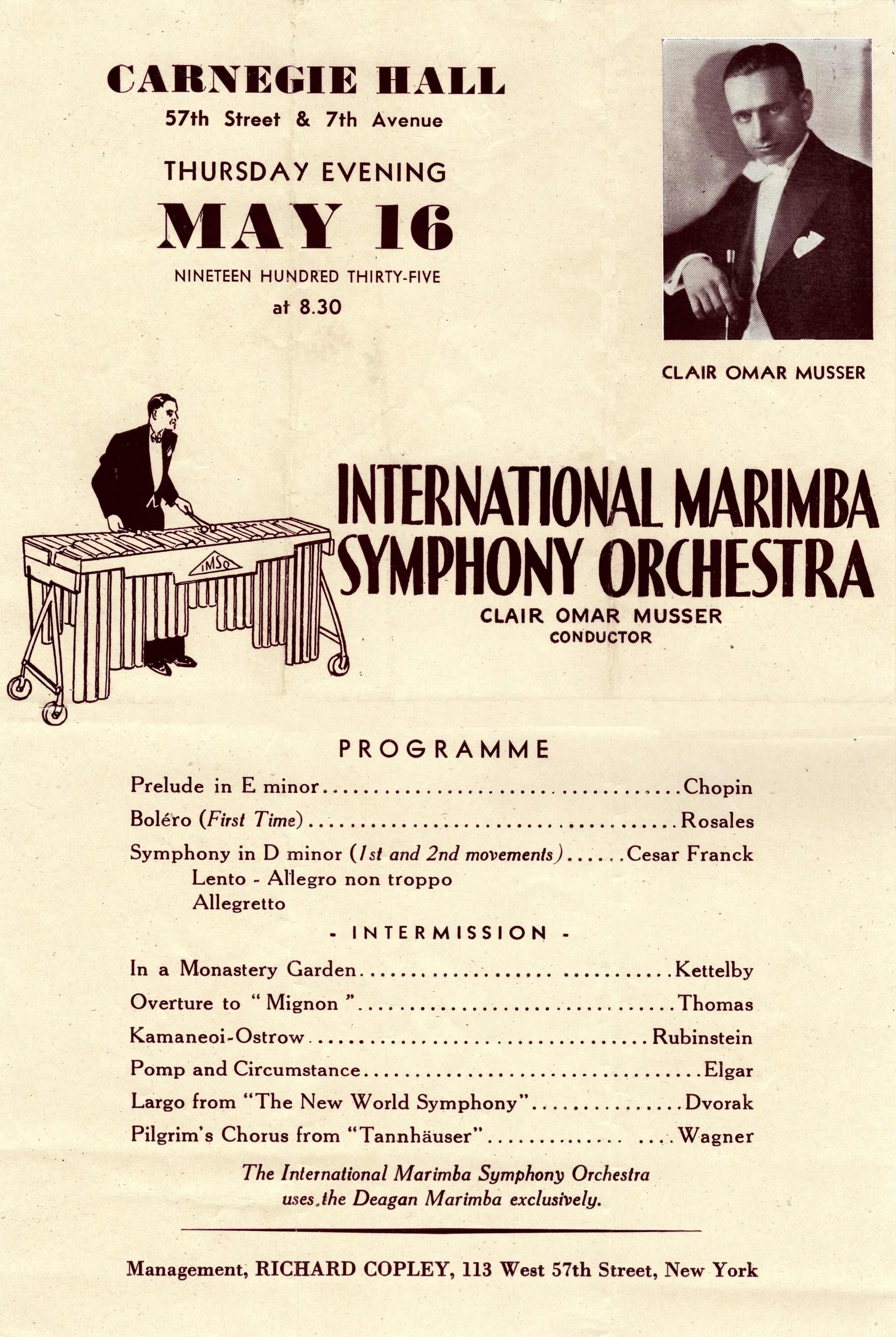

Photo 23

Following the funds being received, the IMSO paid its debt and moved on, eventually returning to a triumphant New York Carnegie Hall concert on May 16, 1935. [Photos 22, 23, 24, & 25] Those premium rosewood marimbas, the months of musical preparation, the rehearsals, concerts, and stage experience of the European tour; all this paid off handsomely in this gala homecoming. [Photo 26] A long-term benefit of this worldly and artistic experience, though, was the influence these marimbists subsequently had on the viability of the marimba in the United States. Following the IMSO run, those musicians returned to their home locales, marimbas in tow. There, many of them performed professionally, generated publicity, raised awareness of the musical potential of the marimba as an authentic artistic medium, and taught the next generation of young marimbists. This had a spawning effect on the growth and stability of the marimba, which undoubtedly accelerated marimba development.

When all is said and done, despite a series of ignominious failures, challenges, frustrations, and disappointments, the ultimate success of the 1935 International Marimba Symphony Orchestra was unqualified in regard to every meritorious factor, such as: the stunning design of the Deagan King George marimbas; the artistic transcriptions written by Musser; the critically acclaimed ensemble performances; the broad international exposure of the marimba, and the historical impact of this event on the development of marimba activity. The International Marimba Symphony Orchestra today occupies a select place in the annals of marimba history, and rightly so. This was, indeed, a highly successful failure.