GOOD WOOD - The Glory Days of Premium Rosewood (1900 - 1956)

David Harvey

If you play marimba or xylophone, you already know two things about Honduras rosewood:

It is the best sounding wood for keyboards, and;

It is scarce to the extent that inferior substitutes, such as Padouk and fiberglass reinforced plastic (FRP,) are used in place of rosewood for many keyboards.

Today’s paucity of top grade Honduras rosewood was not always the case, however. There was a time in the marimba’s history when the very finest rosewood was abundant; so plentiful, in fact, that exporters, manufacturers, and mallet percussionists knew nothing else for their beloved keyboards. Those glory days of premium rosewood occurred from about 1900 to 1956, and the story of the magnificent keyboards of that era, from tree to tuning, is a subject rich in historicity.

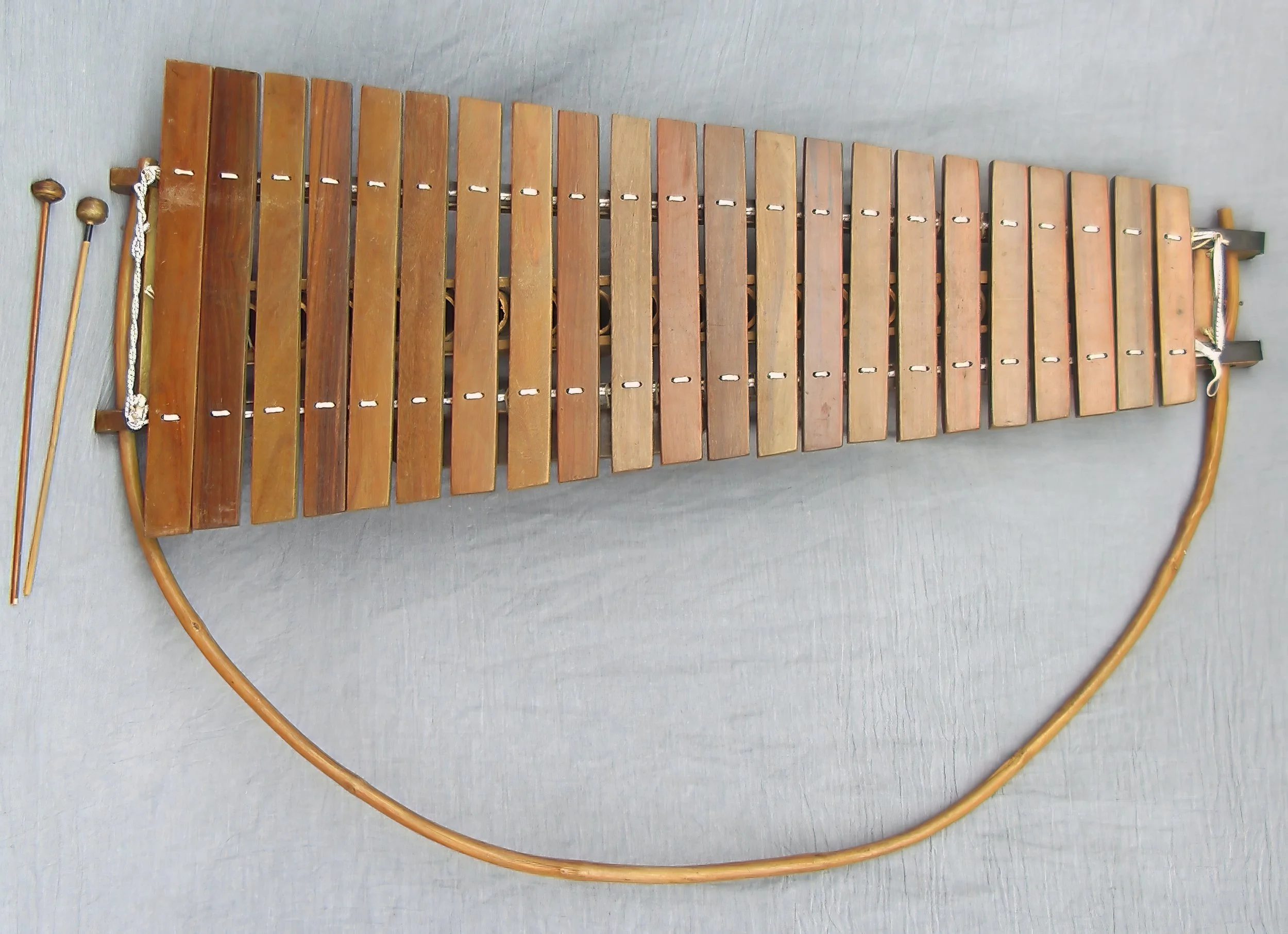

Indigenously, various wooden keyboard instruments sprung up across the globe over time, utilizing woods from tree species local to the vicinities where they were crafted. Southeast Asian xylophones utilized Krah Nhoung, Beng, and Neang Nuon woods, as well as Bamboo. [Photos 1 & 2] The earliest Eastern European xylophones and 19th century American xylophones used Maple bars or Locust wood. [Photos 3 & 4] In Africa, Palisander and African Rosewood are chosen. [Photos 5, 6, & 7] In Columbia and Ecuador, Palm wood is used, and in Nicaragua marimba bars are of Nicaraguan Rosewood. [Photos 8 & 9] In Costa Rica, marimba builders use Caoba, Cristóbal, or Balsamo woods for the bars. [Photo 10]

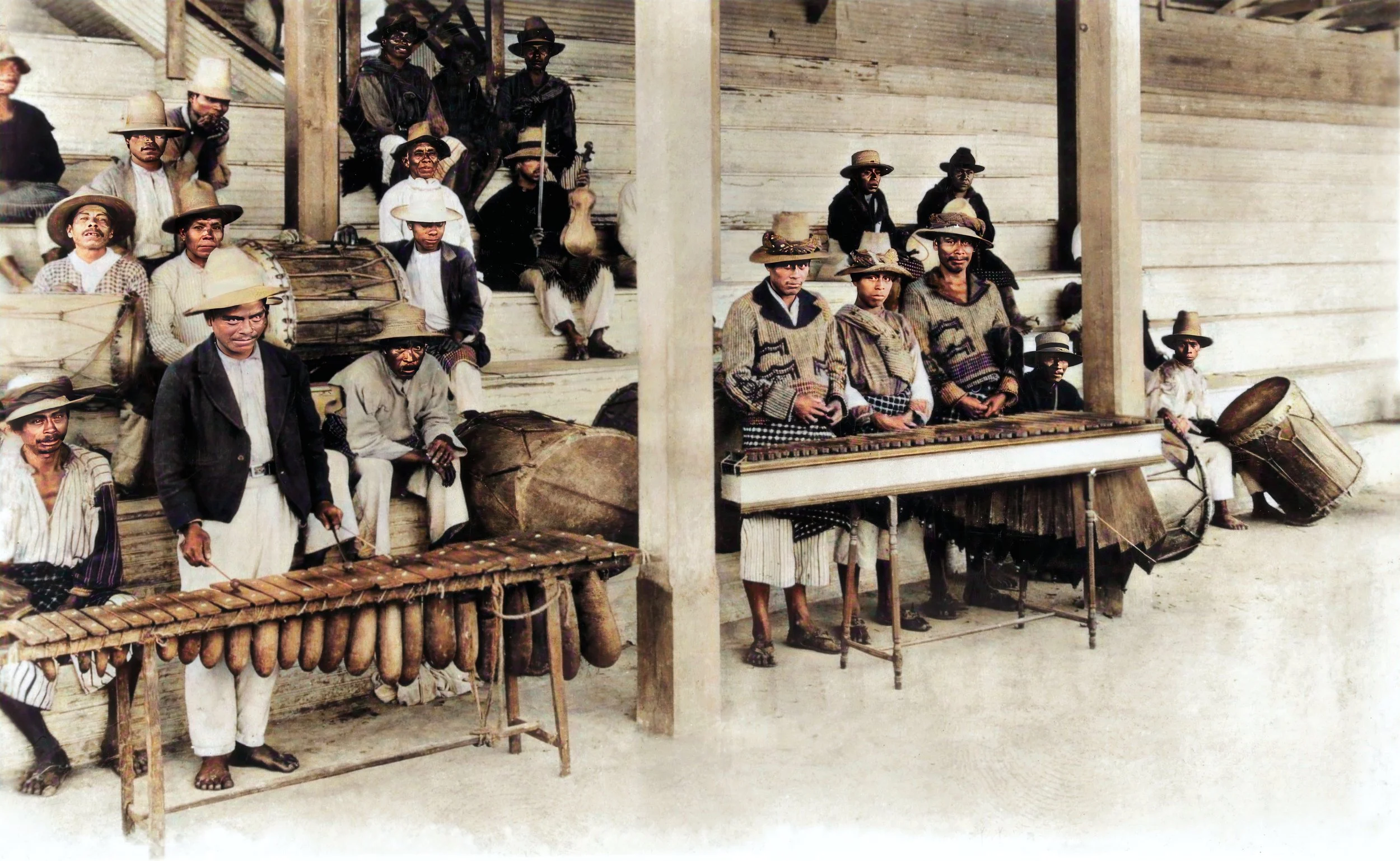

[Photo 11] 17th century Mayans in Guatemala, Central America began fabricating their first marimbas. Like native peoples the world over, they used wood from local trees, called Hormigo, or Macacauba in English. Hormigo is quite similar to Honduras rosewood, and the results of the Guatemalan marimbas using this new material were exceptional. [Photo 12] Guatemalan musicians playing diatonic marimbas had visited the United States as early as the 1880s, during a period that saw many American xylophonists, and drummers doubling on xylophone, becoming active. Most of these 19th century xylophones had maple keyboards, but perhaps as a result of Guatemalan influence, Americans began experimenting with Central American woods.

Photo 11

Photo 12

Of the Central American regions producing rosewood for keyboards, Belize has been the most prolific. From 1783 to 1973, Belize was named “British Honduras,” which is why rosewood from Belize was internationally referred to as Honduras rosewood. To the south of Belize there is another country called “Honduras.” Most, if not all, of the rosewood from 1900 - 1956 for marimbas and xylophones was sourced from Belize, not the country currently named Honduras. [Photo 13]

Photo 13

Photo 14

One may wonder why Belize, in particular, produces ideal rosewood for use as a vibrating musical element. The Belize ecosystem where rosewood trees flourish is a semitropical rain forest situated on the coast of the Caribbean Sea. This area sits on volcanic soil, which long ago was enriched with volcanic ash, making it rich in minerals churned up from deep within the earth’s crust. The climate is warm, sunny, and wet, with up to 160 inches of rain each year, and regular flooding of the forest. A subtle fusion of precise environmental factors including fertile soil, warm temperatures, a long green season, prolific rainfall, and regular flooding combine to create lush growing conditions. [Photo 14] A view of the Belize forest reveals the prosperous results of this dynamic environmental synergy.

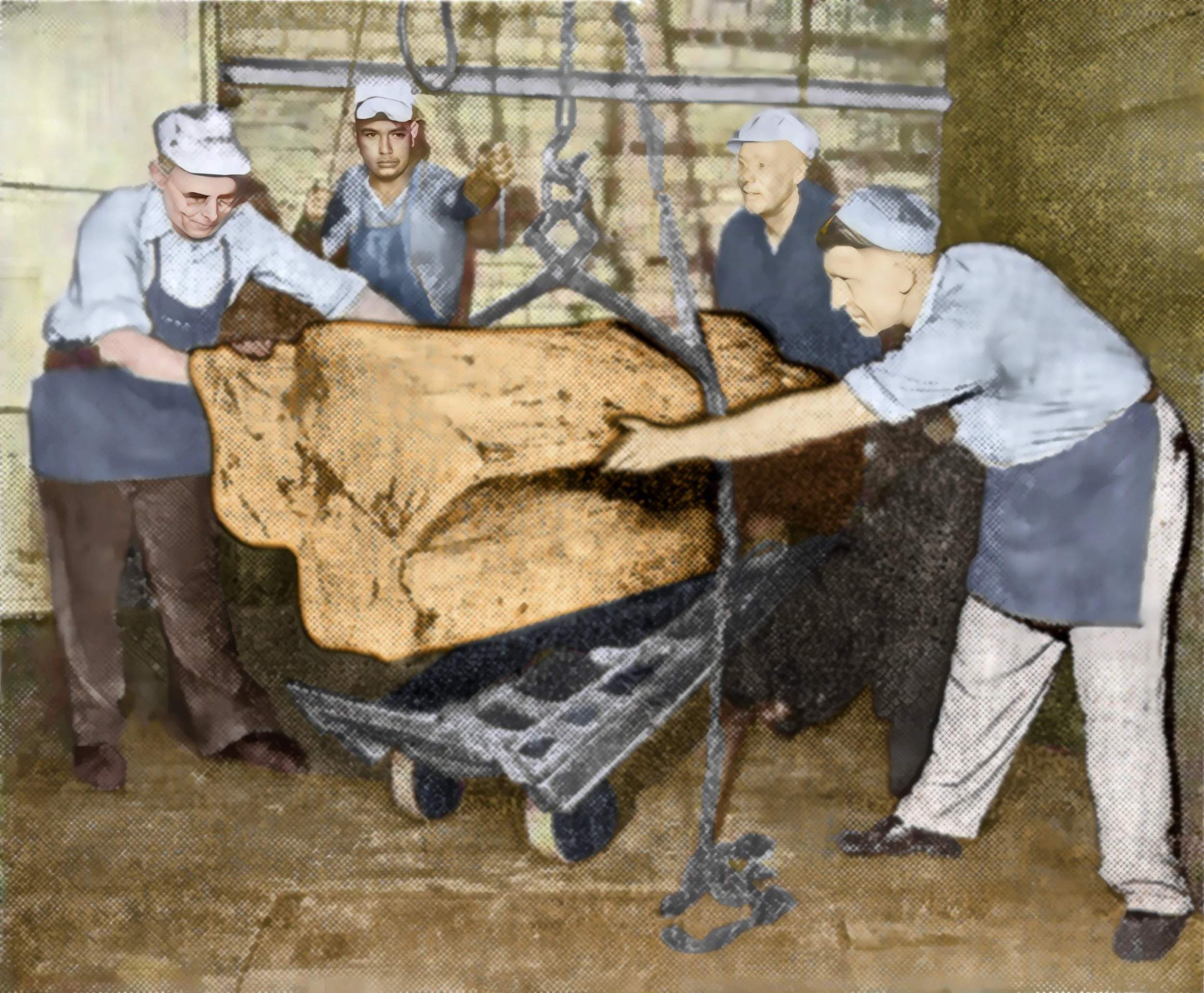

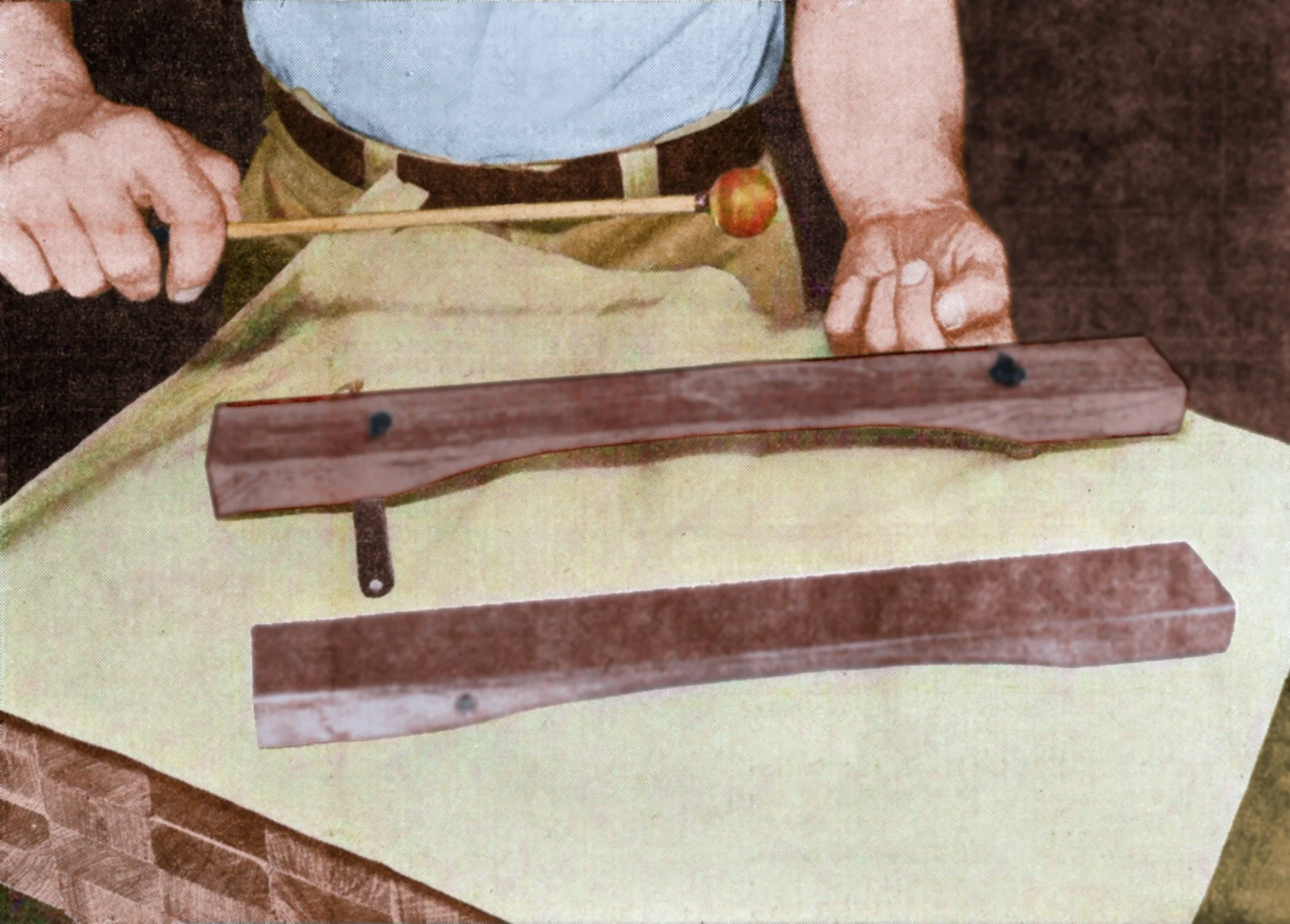

Prior to industrialized countries’ interest in rosewood from Belize in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, natives of this area harvested modest amounts of forest materials using traditional methods. [Photo 15] Such practices included hand-felling trees, using oxen teams to drag logs out of the forest, (called log skidding) and hewing tree products locally by indigenous craftspeople without the need for large processing facilities or regional transportation networks. [Photos 16, 17, & 18] Guatemalan marimba maker Mariano Reyes Andrade is shown in 1958, handcrafting hormigo marimba bars. His tools include an adze for shaping bars, and a glass bottle for tuning them. Andrade was 67 years old at the time, and had been making marimbas for decades, so this style of time-honored Guatemalan woodworking likely harks back to the turn of the 20th century.

Traditionally, light harvesting of trees left the majority of the yield in Belize untouched, resulting in one critical botanical factor affecting quality: trees were allowed to grow for a long time before harvesting, up to a century or more. Honduras rosewood is a slow growing species, so this is a fundamentally relevant issue, as old growth rosewood trees have larger diameter trunks with more heartwood. It is the heartwood of rosewood trees that make the best sounding marimba and xylophone keyboards.

[Photo 19] Heartwood is located in the interior of tree trunks, and is surrounded by sap wood, and finally, bark at the surface. [Photo 20] The heartwood of Dalbergia stevensonii, the Honduras rosewood tree, is much harder and denser than the sap wood. It is not a functionly living part of the tree, but serves as the tree’s skeleton, providing core stability and the requisite strength for the tree to stand upright. Honduras rosewood heartwood displays a maroon-purple hue, while the sap wood is a light beige. The living sap wood is the botanically active layer, feeding the tree by shuttling nutrients and hydration from the soil to the limbs and branches. However, it is too soft and lightweight for marimba and xylophone bars.

Photo 20

Photo 19

Rosewood logs are so heavy that they sink in water, an indication that rosewood is denser than water. This is because the pores in rosewood for sap flow are smaller than those of other tree types, resulting in less open space and more solid matter in a given volume. It is undoubtedly rosewood bars’ combination of density and hardness that contribute to their profuse vibrating reaction when struck, called “tap tone” by woodworkers. The essential oil of rosewood smells like rose, hence the name “rosewood.” One can experience this floral scent by lightly sanding a raw piece of rosewood, which releases a small amount of aromatic oil, and then smelling the freshly sanded area.

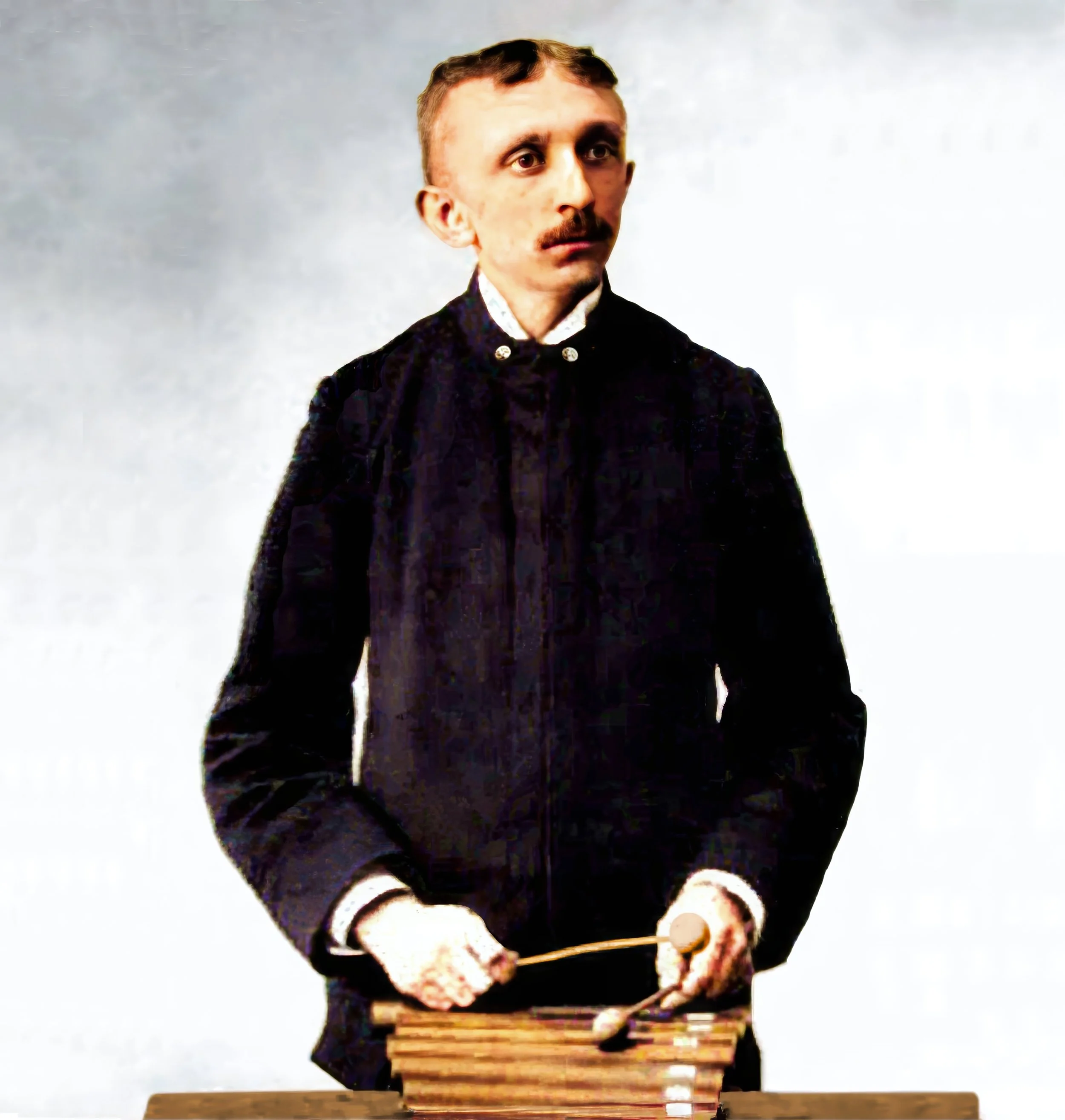

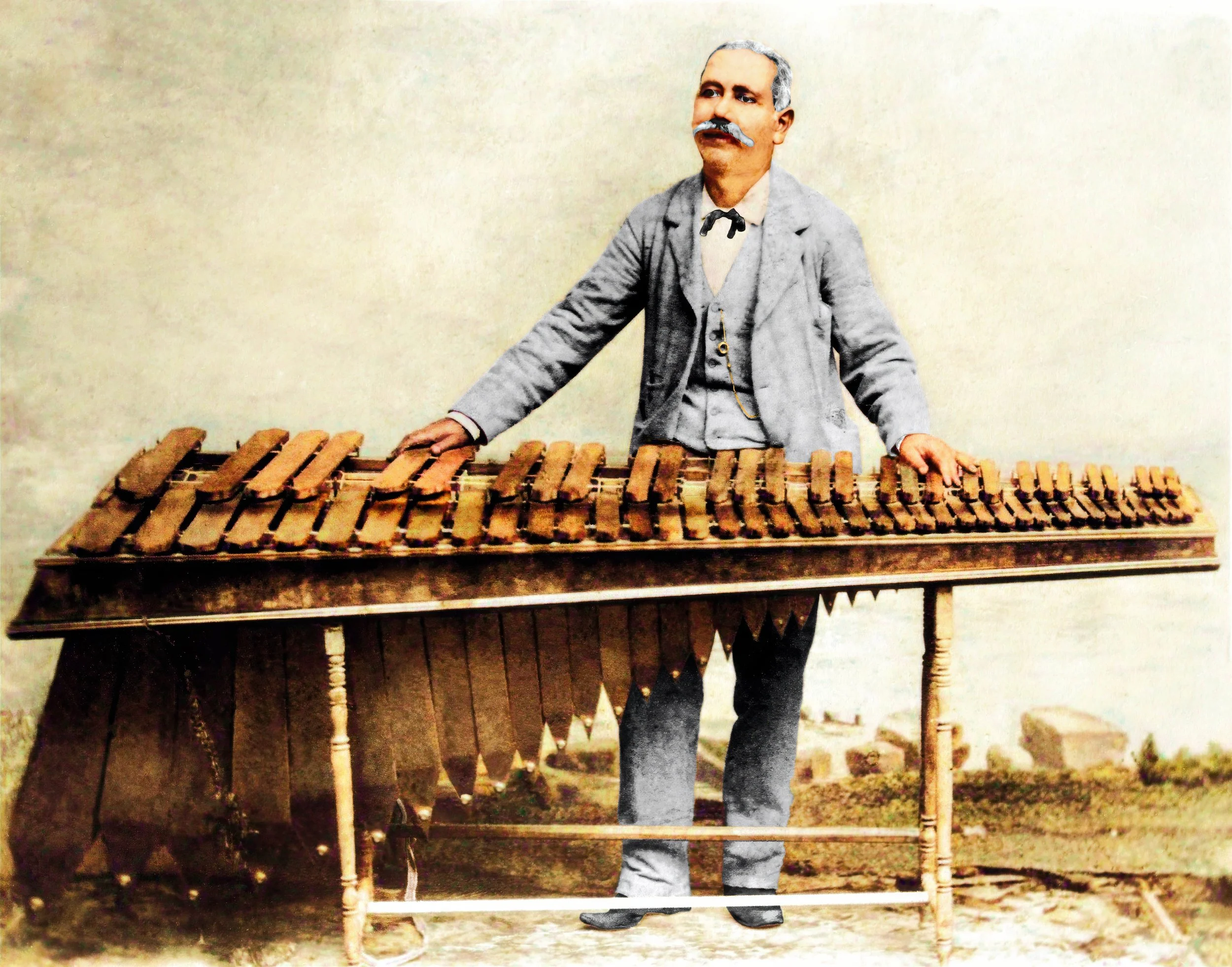

Instrument producers in the United States eventually settled on Honduras rosewood for xylophone bars, though the particular dates for that development seem to be undocumented. Charles Lowe was a professional American xylophonist active from the 1880s. [Photo 21] For a period of about 15 years, from 1890 to 1905, Lowe made hundreds of recordings of solo xylophone music for many record companies. The diatonic keyboard he used was quite simple, laid out on a table, and without resonators. This xylophone was probably crafted by a small independent maker, or possibly by Lowe himself. One recording studio engineer recalled that Lowe would typically arrive carrying two canvas sacks, one in each hand. One sack contained the xylophone bars, while the other sack contained the tools, such as saws and files, used by Lowe to tune the xylophone for each session.

Photo 22

Photo 21

In one such recording made in 1902, entitled Musical Moke, Lowe’s performance is introduced by comedian Len Spencer. [Photo 22] In his intro, Spencer jokingly explains about the xylophone: “It’s made of wood; rosewood. You see, a hayseed dumped some hay seed in a ditch, and up rose wood.” The term “hayseed” can refer to a simple country person, and also to grass seeds obtained from hay. Spencer's jesting about rosewood confirms that in 1902, rosewood xylophone bars were in use in the US, though maple was still utilized as well.

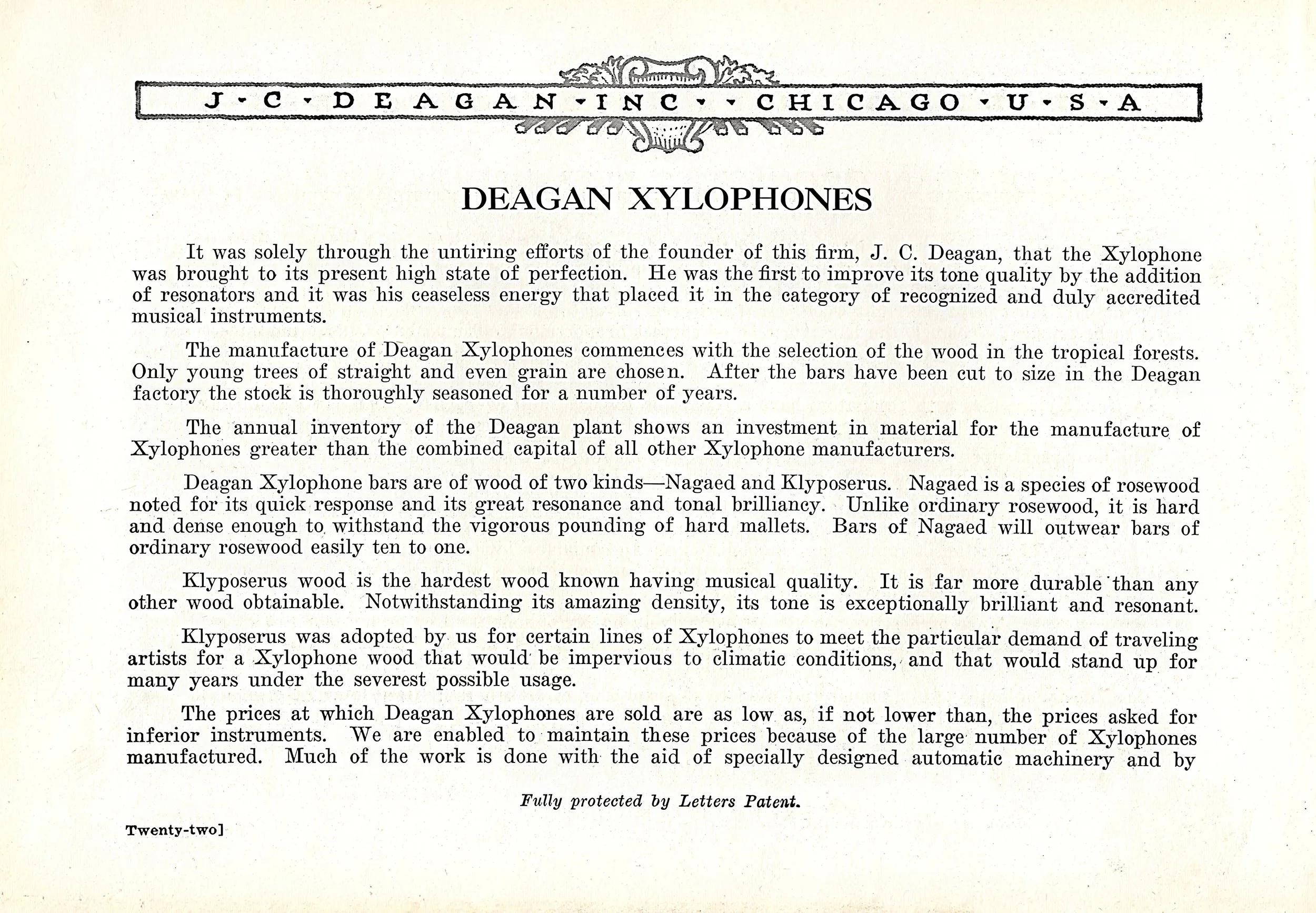

[Photos 23 & 24] At the beginning of the 20th century, there were two principal American xylophone manufacturers: J. C. Deagan Inc. of Chicago, and the Leedy Manufacturing Company in Indianapolis. Although there were smaller independent companies as well, Deagan and Leedy set the standards for materials and design, which became standardized. [Photo 25] Around 1920, the Deagan company published a description of the wood used in their keyboards.

Photo 23

Photo 25

Photo 24

“The manufacture of Deagan Xylophones commences with the selection of the wood in the tropical forests. Only young trees of straight and even grain are chosen. After the bars have been cut to size in the Deagan factory the stock is thoroughly seasoned for a number of years.

The annual inventory of the Deagan plant shows an investment in material for the manufacture of Xylophones greater than the combined capital of all other Xylophone manufacturers.

Deagan Xylophone bars are of wood of two kinds - Nagaed and Klyposerus. Nagaed is a species of rosewood noted for its quick response and its great resonance and tonal brilliancy. Unlike ordinary rosewood, it is hard and dense enough to withstand the vigorous pounding of hard mallets. Bars of Nagaed will outwear bars of ordinary rosewood easily ten to one. The trade name "Nagaed" is to Deagan Marimba and Xylophone bars what Sterling is to silver, the hallmark of highest quality.

Klyposerus wood is the hardest wood known having musical quality. It is far more durable than any other wood obtainable. Notwithstanding its amazing density, its tone is exceptionally brilliant and resonant.

Klyposerus was adopted by us for certain lines of Xylophones to meet the particular demand of traveling artists for a Xylophone wood that would be impervious to climatic conditions, and that would stand up for many years under the severest possible usage.”

[Photo 26] The word “Nagaed” is simply “Deagan” spelled in reverse. This term was coined by Deagan to conceal the identity of Honduras rosewood, as a trade secret known only to that firm. [Photo 27] “Klyposerus” was a pseudonym, probably for Caribbean “Lignum Vitae” wood, once again to obscure proprietary information. While Honduras rosewood is the best sounding keyboard wood, Lignum Vitae was chosen for durability, not tone, due to its extreme hardness.

Photo 27

Photo 26

The Janka Hardness scale is used to specify the hardness of various woods. For example, White Oak is a hardwood with a Janka Hardness rating of 1,350 lbf (pound force,) which is higher than many commonly used woods. Honduras rosewood’s Janka Hardness is 2,200 lbf, indicating that it is considerably harder than Oak. Lignum Vitae, however, has a Janka Hardness rating of 4,500 lbf, indicating that it is more than double the hardness of rosewood. The hardness of lignum vitae was needed in early American xylophones that were increasingly being played with rock-hard mallets made of vulcanized rubber.

Vulcanization is a chemical manufacturing process first developed in 1839, applying heat and sulfur to harden rubber automobile tires for increased durability. During the early 20th century, the use of vulcanized balls for xylophone mallets prompted Deagan to offer customers two choices of woods for xylophone bars. Xylophonist George Hamilton Green mentioned this situation in advice to students:

“ NEVER use an extremely hard HAMMER. They will ruin your instrument by causing the bars to become full of small dents, and the tone from a hard hammer is entirely too HARSH. I never use hammers that are harder than three-quarter hard rubber.”

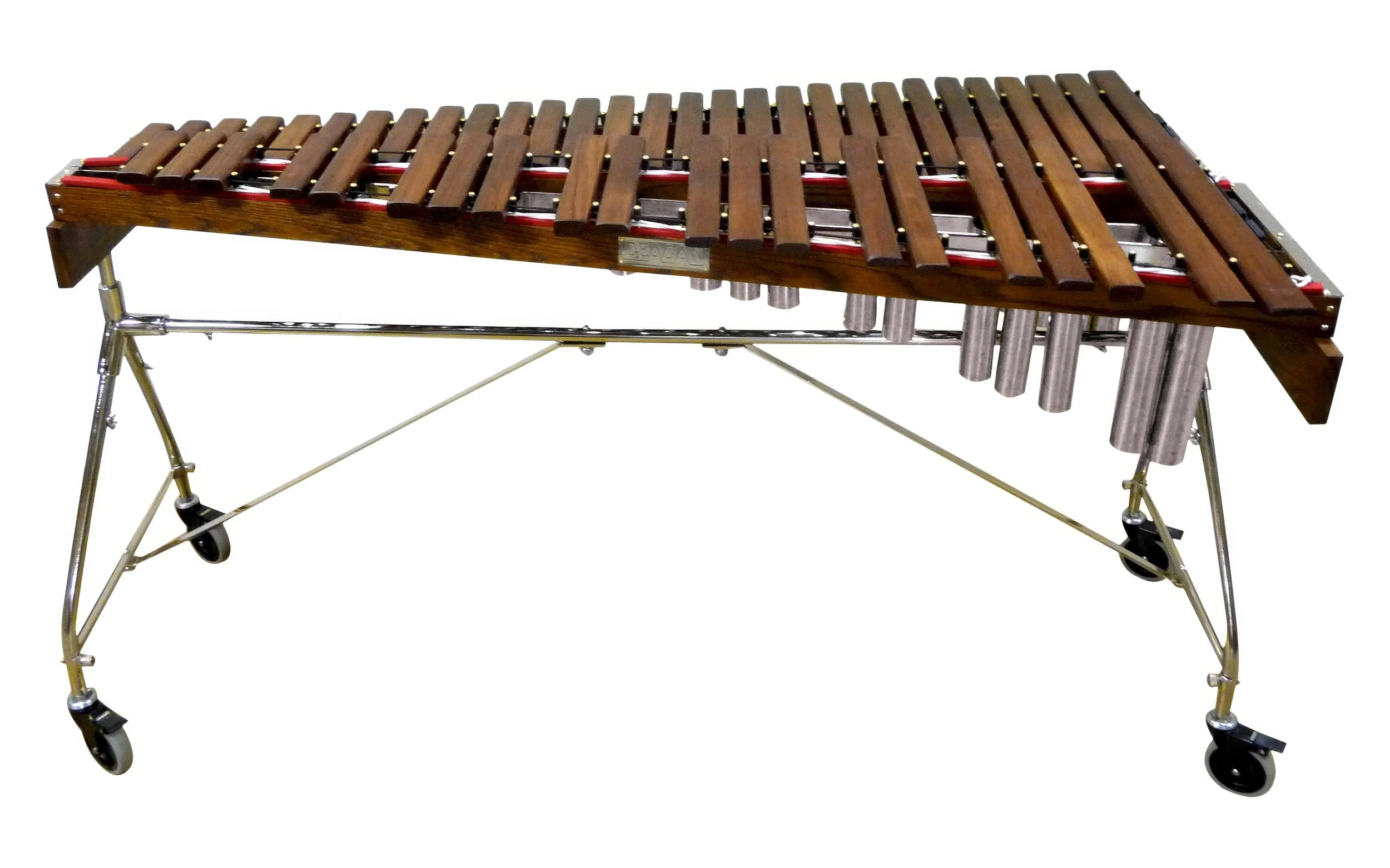

During the 1890s and 1900s, when Ulysses Grant Leedy [Photo 28] and John Calhoun Deagan [Photo 29] were pioneering American xylophone construction, such basics as metal resonators, two row keyboard layout, elevated accidentals, standardized intonation, and folding floor stands were designed, developed, improved, and in some instances, patented. By the mid-1910s, Deagan design, construction, and appearance were clearly superior to Leedy’s products. Deagan’s 870 and 872 Professional Xylophones [Photos 30 & 31] were the most widely used xylophones of this period, and for good reason. Those keyboards featured premium aged rosewood cut to moderate width and long bar lengths, lending them a strong response and resonant tone.

Photo 30

Photo 31

Photo 28

Photo 29

[Photos 32] Xylophone virtuoso William Coates, stage name El Cota, then suggested to Deagan a new concept in xylophone bar design: extra wide bars. [Photo 33] The result was the De Luxe Xylophone 3116, sporting bars that were mammoth by comparison to standard width rosewood xylophone bars. [Photo34] Eventually, Deagan renovated their wide bar design by incorporating rounded ends, resulting in the Artists’ Special xylophone line. [Photo 35] These were the most extravagant xylophones ever produced by J. C. Deagan, Inc., designed to emit more sound than any prior xylophone. Models offered included 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, and 5 octaves, all displaying extensive keyboards resulting from extra wide bars. [Photos 36 & 37] The 5 octave Artists’ Special in particular represented an ebullient celebration of premium rosewood that one must witness to fully appreciate.

Photo 35

[Photo 38] Around the same time as the Deagan description of its xylophones, the Leedy company provided its own narrative recalling the early days of American xylophone construction.

“Years ago (in this country) Rock Maple was used in Xylophone construction, because it was a domestic wood and easily obtainable. Later it was found that Locust served as an improvement, and still later Brazilian Rosewood was introduced. Some manufacturers still use this latter wood, which is procurable on the open hardwood market. It has only fair tonal qualities and is too soft to wear well. And now comes the best of all - British Honduras Rosewood which comes from British Honduras, Central America. This specie is recognized by the leading authorities as the most suitable and best tone-producing, as well as the most durable wood for Xylophones. We call it exactly what it is, knowing there is nothing better to beobtained, and to give it a fictitious name would not in any way improve it. Only the finest logs are selected, and after being cut into approximate sizes these are allowed to dry by the natural air process for at least three years before being used. This wood is so heavy that it will sink in water, and it is purchased by Leedy direct from Central America, by the pound and not by the foot, as is the case with other forest products.”

Photo 39

Photo 38

The Leedy mention of the use of a fictitious name for rosewood is obvious pushback against the Deagan term “Nagaed,” to make clear that Deagan did not, in fact, have a uniquely superior material for its xylophone and marimba bars. Interestingly, the reference to the prior use of Brazilian rosewood most probably refers to earlier Leedy instruments. [Photo 39] The first Leedy keyboards of about 1900 - 1910 had beige colored wood, which was different from the purple shade of Honduras rosewood. Brazilian rosewood seems a likely possibility for this substance, as this allusion to Brazilian rosewood by Leedy may be the only instance of this species being documented as material for keyboards during this period.

Around 1917, in an effort to increase market share, Leedy redesigned their Solo-Tone line of xylophones and marimbas, with the express aim to surpass Deagan quality. This upgrade, of course, included premium Honduras rosewood keyboards. By this time, Leedy had been slowly aging many tons of Honduras rosewood that was now ready for this product upgrade. The results were unequivocal: the newly updated line of Leedy Solo-Tone xylophones and marimbas clearly surpassed Deagan standards in every regard. [Photos 40, 41, & 42] This included seasoned premium straight-grained rosewood, bar geometry, tone quality, and even the staining and beautiful shellac polish of the rosewood keyboards.

Photo 43

[Photo 43] No less an artist than George Hamilton Green, who previously used Deagan xylophones, switched to Leedy instruments exclusively in 1922, publicly endorsing the Leedy Brand:

“My many years as a professional xylophonist have naturally given me a chance not only to try different makes but I have owned many different brands and played extensively on them all. At present I have three of the Leedy manufacture, and there is not one point on any of these instruments that is not far superior to any other make, even including the hammers and cases. I am through experimenting and shall use Leedy exclusively in the future.”

“They are wonderful and not a single musician of the many who have viewed and heard them have found even the slightest adverse criticism as to tuning, quality, volume, finish, design or workmanship. All of these points are “Leedy perfect” as usual.”

[Photo 44] George Hamilton Green and his brother, Joe Green, amassed a large collection of Leedy keyboards, using them constantly in their busy careers. George was keenly interested in the Leedy manufacturing process, even visiting the Leedy plant to familiarize himself with the manufacture of rosewood keyboards. [Photo 45] He was there photographed learning hands-on how to drill cord suspension holes in rosewood bars, with Leedy Vice President Herman Winterhoff and sales manager, George Way.

Photo 45

Photo 44

In the 1910s, Guatemalan groups touring the United States aroused interest in the marimba. After 300 years of diatonic marimbas in Central America, the first Guatemalan chromatic marimba appeared in 1896. [Photo 46] The massive almost six-octave layout was designed by musician and marimba builder Sebastien Hurtado in Quetzaltenango. Various Guatemalan chromatic marimba ensembles began concertizing in the United States in 1915, and received spectacular public acclaim. [Photo 47] Their combination of well-designed marimbas, superb ensemble musicianship, and a musical genre never before witnessed generated a groundswell of interest.

Photo 47

Photo 46

Suddenly, American xylophonists wanted marimbas. Leedy and Deagan had previously offered marimbas, which sold modestly, as the xylophone was the established solo voice of mallet percussion. Now, with Leedy and Deagan competing for shares of the burgeoning American marimba market, they spared no expense or effort to produce the absolutely finest rosewood marimbas imaginable, incorporating wider bars, extended lower registers, and large ranges of up to five octaves.

With two decades or more of keyboard production experience, certain critical factors of rosewood crafting were at this point codified. The careful selection of trees in Belize was the first step in this process. Both Deagan and Leedy regularly sent representatives to Belize to personally identify the choicest trees for export. [Photo 48] The select trees were then felled, debarked, and loaded onto ships in Belize ports. [Photo 49] Cargo ships sailed the Caribbean Sea into the Gulf of Mexico, arriving in New Orleans. [Photo 50] There, the logs would be placed on barges for passage up the Mississippi River towards the regions of Indianapolis or Chicago. [Photo 51] A final rail trip from river ports would complete the precious wood’s journey from Central America to the awaiting Leedy and Deagan lumber facilities. The logistical advantage of a water route extending from Central America to within 200 miles of the Leedy and Deagan properties is an inestimable factor in the American adoption of Honduras rosewood for mallet keyboards.

Photo 50

Photo 51

Photo 52

Photo 53

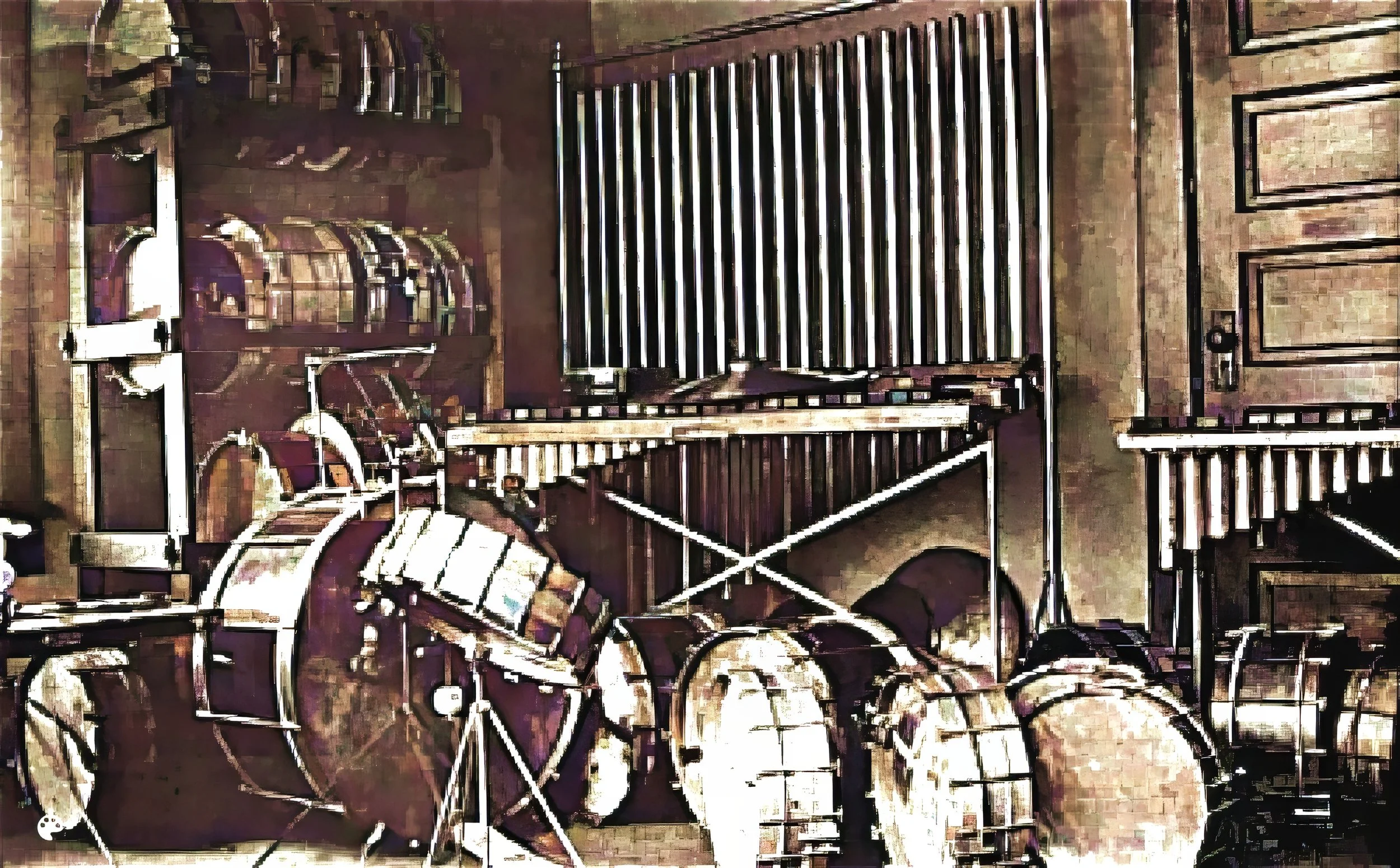

This procurement process occurred several times per year, with trainloads of logs arriving regularly to satisfy the pace of production. Once stocked in Indianapolis or Chicago, the Central American logs at both manufacturers were allowed to sit for about two years to commence the first stage of the open air drying process. Deagan had a basement lumber cellar typically stocked with 56 tons of rosewood logs. Upon arrival, these logs were graded, marked, and stood upright on end. [Photos 52 & 53] Each log weighed between 1,100 to 2,700 lbs. After about one year, the logs were laid on their sides and turned regularly to rotate the orientation of all sides of each log. Leedy used an outdoor lumberyard behind its factory, where a similar quantity of rosewood logs was stored, laid on their sides in open air sheds. [Photo 54]

Photo 54

After two years of seasoning, both Leedy [Photo 55] and Deagan [Photo 56] quarter sawed their logs. There are two basic methods of sawing logs to produce boards: plain-sawn and quarter-sawn. [Photos 57 & 58] Plain sawing is the most common method because it produces the highest yield of usable boards. However, the direction of the wood grain varies across the surface of the board, which is why some boards warp over time, while other boards remain straight. Quarter sawing involves first cutting the log into four equal wedges, and then cutting each quarter-wedge into boards with the grain of the wood running perpendicular to the face of the boards. [Photo 59] This ensures that the boards will not warp, and will absorb less moisture from humidity. Unfortunately, however, quarter sawing reduces the number of boards that can be obtained from a single log. For marimba and xylophone bars, quartersawn boards are essential.

After logs were quatersawn, [Leedy; Photos 60, 61, & 62] [Deagan; Photos 63 & 64] the wedge-shaped segments were again aged prior to ripping into boards. Once boards were cut, seasoning continued further in the open air for extended periods. After six to seven total years of aging, the moisture content of the blanks finally reached a sufficiently low level to fabricate into bars. As a final preparation, Deagan placed the blanks into a kiln to heat the wood to an extreme temperature. The company did this not to further dry the wood, but claimed rather: “This seals resin between fibers controlling the molecules, resulting in better sustenance of tone.” Leedy claimed however: “We do not believe in the kiln-dry method, because this artificial and forced method is injurious to the tone.”

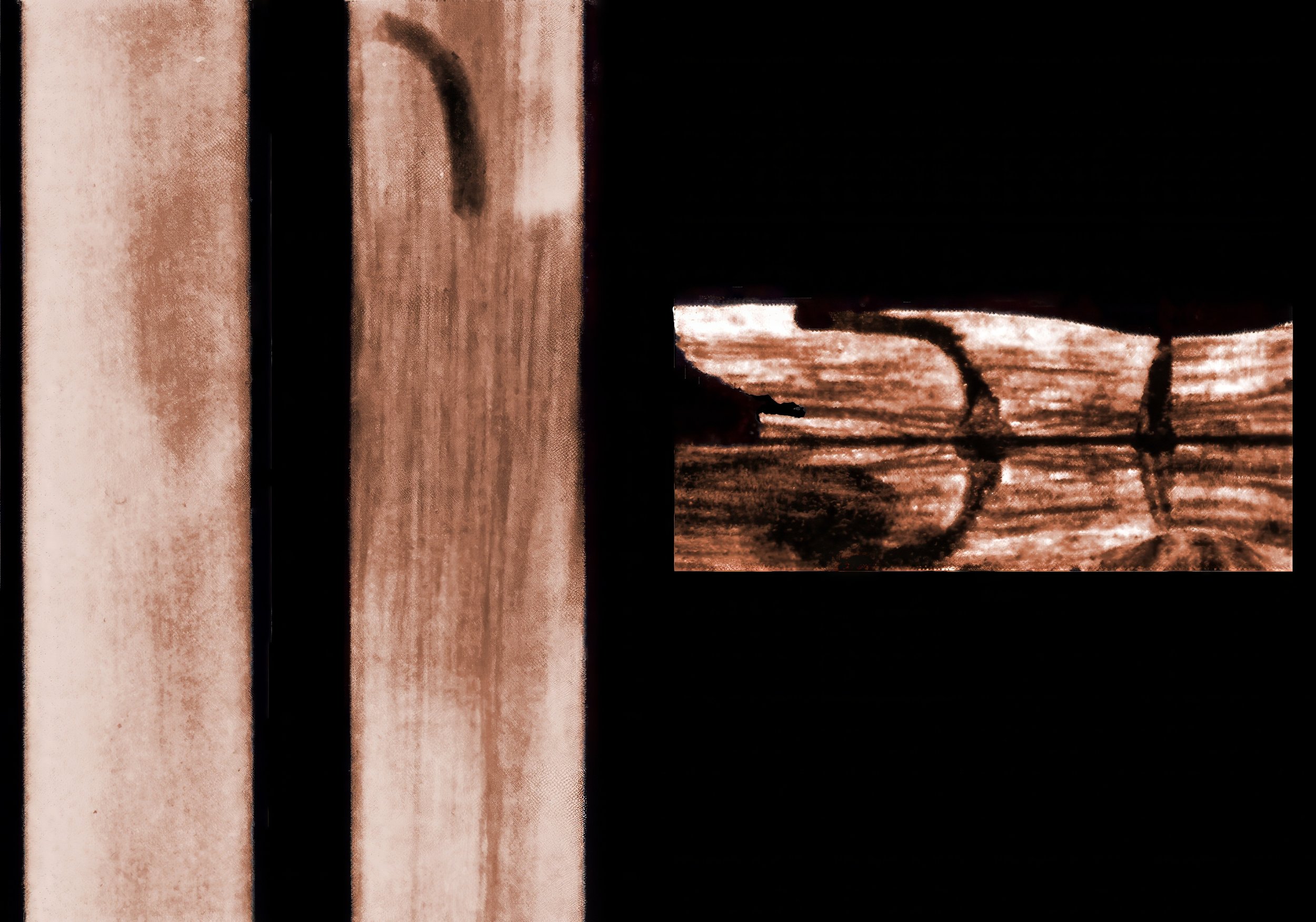

Each individual bar’s condition received careful scrutiny by experienced engineers prior to approval for tuning. Deagan even used X-ray equipment to examine the interior of each rosewood bar. [Photo 65] Photos taken at the Deagan factory show three views of the same rosewood bar. [Photo 66] The image on the left is the surface of a bar that appears flawless. In the center is the X-ray image of that same bar, revealing an anomaly inside the bar that appears as a curved black line. The image on the right is the same bar again, cut open to reveal a worm hole that occurred when the tree was young, rendering that piece of wood useless. Various flaws such as ingrown knots, open grains, and others that would cause a rosewood bar to be inferior could all be identified in advance of tuning.

As a result of quarter-sawing, tuning arch cutting, and other stringent quality standards for marimba and xylophone bars, Deagan estimated that they routinely discarded 63% of their rosewood stock. Leedy quarter-sawing and quality control resulted in similar losses of raw material. These are staggering statistics, especially considering that all the rosewood involved was sourced from the finest Honduras rosewood producing trees in the world; tress that required decades to grow to the sizes involved. Clearly, this was an unsustainable rate of consumption of a natural resource, which is not readily replenishable.

Photo 65

Photo 66

Photo 67

Photo 68

Photos [67 & 68] By the late 1910s, the marimba was beginning to significantly compete with the xylophone in American musical life. [Photo 69] Marimbist Paul Farmer, who was a former pianist and drummer, subsequently devoted his career to the 4.0 octave marimba in 1917.

“I came to love the tone of the instrument, and gradually increased my practice almost to the exclusion of the others. I think now that the lower register of the marimba gives forth the most beautiful musical tone of any instrument. For waltzes and other slow and classical music it fills a vacancy which no other can; while the upper register, for the faster and more popular music, is excellent.”

Photo 69

With greater exposure of the marimba, overtone intonation of marimba bars became a prominent issue. Xylophone bars possess both an extremely high musical range and a staccato ring time, producing fleeting overtones that are somewhat faint. Therefore, during the early chapters of both Leedy and Deagan, with emphasis primarily or exclusively on xylophone production, overtone tuning was not even considered.

The emphasis regarding intonation during those formative years were options such as Low Pitch A = 435, High Pitch A = 454, or other pitches, and eventually standardized A = 440 in 1910. Marimba bars are a different story, having a longer ring time, and lower register notes that produce upper partials that are inherently noticeable to the human ear. Consequently, due to the established practice of fundamental only tuning, the first generation of American marimbas were noticeably discordant, despite their fundamental pitches being properly calibrated.

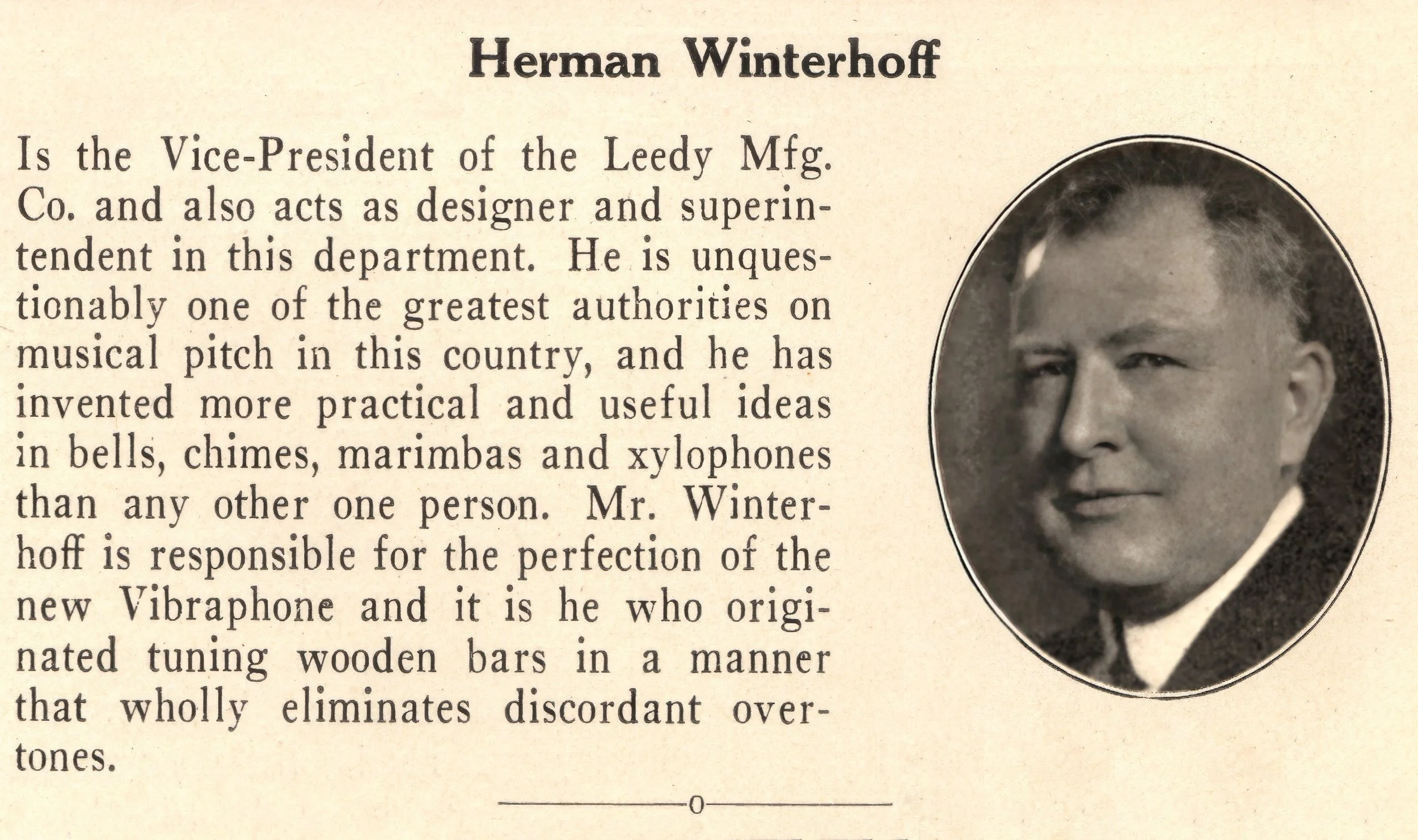

[Photo 70] Herman Winterhoff served as Vice President and head of mallet instrument design at the Leedy Manufacturing Company since that company’s inception. [Photos 71, 72, & 73] On January 22, 1923, Winterhoff filed Application 614,134, entitled “Musical Bar,” with the United States Patent Office. In his application, he presents the previously unconceived notion of tuning the first overtone of a wooden bar to the double octave, also referred to as the fourth harmonic.

Winterhoff accomplished this by adjusting the thickness of the tuning arch at the antinodal points corresponding to the first overtone, explaining:

“ . . . no attempt has been made to octavely tune the first overtone of the bar, nor, so far as I am informed, has it been appreciated that this accurate tuning of the first overtone of the bar could be produced. . . . no attention has been paid to the resultant first overtone and therefore, heretofore, the musical interval between the resultant fundamental tone and the resultant first overtone has been a neglected variable. . . . This spacing, in the type of bar shown in Fig. 1 is two octaves.”

Included in Winterhoff’s application are two illustrations for different methods of tuning the first overtone, though only the tuning arch shown in Figure 1 was actually used commercially. US Patent 1,632,751 was granted for his invention on June 14, 1927, and assigned by Winterhoff to the Leedy Manufacturing Company. Of the many American innovations in rosewood keyboards to this point, overtone calibration was of singular significance, as this transformation instantly elevated the character of the industrialized marimba from an updated folk instrument to a sophisticated medium of refined timbre. In 1923, therefore, the marimba for the first time assumed provenance among the violin, piano, and other artistic instruments in the grand European tradition.

Photo 74

The Leedy company’s aspiration to produce the finest marimbas was now unquestionably secured. [Photo 74] In “Drum Topics,” a Leedy periodical publication, the company cited Herman Winterhoff for his contributions to the science of mallet percussion:

“He is unquestionably one of the greatest authorities on musical pitch in this country, and he has invented more practical and useful ideas in bells, chimes, marimbas and xylophones than any other one person. . . . it is he who originated tuning wooden bars in a manner that wholly eliminates discordant overtones.”

Leedy incorporated octave-tuned bars in their Solo-Tone marimbas, a line that had already been in production prior to overtone tuning, but now were updated to become the first overtone tuned rosewood keyboards offered to the public. The Solo-Tone marimbas were available either with a high C7, as with today’s marimbas, or a high C8, which is the high xylophone C. The Leedy models with C7 were listed as “marimba,” while those models extending to C8 were listed as “marimba-xylophones.” This use of the term “marimba-xylophone” referred solely to the fact that such keyboards contained both the marimba and xylophone ranges; it did not imply anything regarding tuning of the bars.

[Photo 75] A Leedy product catalog proclaimed the superiority of its flagship Solo-Tone Monarch Marimba-Xylophone, emphasizing this unprecedented intonation feature:

“A moment's inspection and the tapping of a few bars will convince the most skeptical that this instrument is positively the last word in ultra-fine Marimba-Xylophone construction. The oversized bars and resonators give forth bass notes sonorous and rich, not unlike the pipe organ, while the upper register has great brilliance. Every bar has wonderful volume and carrying power. Like all Leedy Marimbas or Xylophones, the bars are of Honduras Rosewood . . . and the exclusive original Leedy invention of tuning the bars in a manner wholly eliminating out-of-tune overtones.”

Photo 75

Photo 76

Photo 77

[Photo 76] A detailed view of the Leedy 5-octave Monarch keyboard reveals just how spectacular this groundbreaking marimba really was. [Photo 77] During the 1920s, Fred Paine was principal percussionist with the Detroit Symphony, and also regularly performed as marimba soloist with that orchestra. He used exclusively the Leedy Monarch 5-octave keyboard, and in 1926 Paine stated:

“ . . . I want you to know that it is, without doubt, in every point the finest marimba-xylophone I ever saw, heard, or played upon. The workmanship and intonation are superb, and as for tonal quality – well, as I say, I never heard its equal. Every overtone being positively in tune with the fundamental of each bar, makes it the only perfect marimba-xylophone. In my estimation it meets and fulfills every requirement that ever has been or is likely to be demanded of such an instrument, and to say that I am more than pleased is to put it mildly.”

From the time of Winterhoff’s tuning arch design innovation in 1923, Leedy went on to enjoy exclusive overtone tuning of rosewood bars for a period of about eight years. [Photo 78] On October 30, 1930, Deagan’s chief tuner, Henry Schluter, filed US patent Application 492,129, entitled “Vibrant Bar for Musical Instruments.” Unlike Winterhoff’s patent for octave tuning, Schluter’s invention involved quint tuning of rosewood bars, whereby the first overtone sounds at the interval of a twelfth above the fundamental pitch, which is the third harmonic.

[Photos 79 ‑ 83] Schluter’s text outlined his unique tuning method:

“It is an important object of this invention to provide a percussion type of musical instrument provided with improved vibrant bars . . . whereby extra tones in the forms of twelfths or quints are produced in addition to the fundamental tones.”

“The improved vibrant bars of this invention are peculiarly shaped to provide . . . additional nodes to the fundamental nodes of the bar. The additional nodes produce extra tones . . . whereby octaves, twelfths, quints and other selected intervals can be produced.”

Schluter’s application included illustrations of two methods of shaping the bar, but only the type in Figure 5 was produced. Patent 1,838,502 for quint tuning of bars was issued on December 29, 1931, and assigned by Schluter to J. C. Deagan, Inc. The quint-tuned design of thick bars and bright timbre is best suited to xylophones, due to their high range. Deagan, therefore, quickly offered two new xylophones featuring overtone tuning in 1932: the Super-Radio Xylophone and the Radio-Master Xylophone. [Photo 84] These models supplanted Deagan’s prior Deagan-Radio Xylophone, the only changes being quint-tuned bars, and post suspension of the bars replacing bars sitting on felt.

Many 1930s xylophonists, such as Red Norvo, [Photo 85] Sammy Herman, and Harry Breuer, made their careers on the 3.5 octave #924 Deagan Super-Radio xylophone. Interestingly, Deagan made no mention of overtone tuning in their catalogs of this period regarding the Super-Radio or Radio-Master xylophones, stating simply:

“The finely selected bars are post mounted and scientifically tuned for perfect recording and radio results.”

As a result of Deagan’s 1931 patent, both Leedy and Deagan each had exclusive legal rights to one of two specific forms of overtone tuning. Leedy had patent protection for octave-tuned marimba bars, while Deagan had the same protection for quint-tuned xylophone bars. With each company producing both marimbas and xylophones, a surprising development ensued.

Photo 84

Photo 85

Photo 86

Photo 87

[Photos 86 & 87] About a year after the Deagan patent was issued, Clair Musser began working for J. C. Deagan Inc., designing a unique marimba for the 1933 Century of Progress one-hundred member marimba orchestra. This beautiful marimba featured octave-tuned bars, in direct infringement of the Leedy patent. Moreover, in 1934, Musser designed the King George specialty marimba, this time for the International Marimba Symphony Orchestra. [Photo 88] Again, this new Deagan marimba incorporated octave-tuned bars, another infringement into the Leedy patent protection.

Surprisingly, no lawsuit emerged from the ownership at Leedy. How and why did the Deagan organization openly defy the very important exclusive patent of their major rival, and do so with impunity? The explanation becomes apparent when Leedy, during this same period, retooled their line of xylophones to include quint tuning. The Leedy George Hamilton Green and Broadcaster xylophone models from the 1930s were the first Leedy xylophones with quint-tuned bars, using patented technology assigned to J. C. Deagan, Inc.

Photo 88

[Photos 89 & 90] From a Leedy catalog describing the newly updated 5618 George Hamilton Green model xylophone, one comment in particular hints at quint tuning:

“It features finer, fuller, richer and more resonant tone due to its new, scientifically correct larger bar and resonator sizes which also give it maximum carrying power and volume.”

Only a few years earlier, Leedy had publicly derided such a simple point of contention as Deagan’s use of the term “Nagaed.” Yet now, when both companies began using the other’s patented methods, there was no public fallout at all. It seems plausible, therefore, that the two firms may have privately negotiated a reciprocity agreement, allowing each of them to use the other’s tuning technology. As it was Clair Musser, with a penchant for promotion and public relations, who designed the first octave-tuned Deagan marimba, it may be he who negotiated such an agreement on behalf of J. C. Deagan, Inc., if in fact one existed.

Photo 90

Photo 89

In 1934, following its limited production runs of the Century of Progress and King George marimbas, Deagan incorporated octave tuning in their two top-selling marimbas. [Photos 91 - 94] The previous keyboards were the 3.5 octave marimba #352 and 4.0 octave #354, which had been staples in the Deagan catalog since 1918. They were replaced by versions #52 and #54, which are the old catalog numbers with the first digit deleted. These replacements were virtually identical, with no visibly discernable differences, as the only change was octave tuning of the rosewood bars.

With a new harmonic sonority, these updated marimbas were masterpieces of design, and fittingly given the title “Masterpiece Marimbas” in Deagan’s line. [Photo 95] These new marimba models were touted on the cover of the company’s next catalog, and inside were described in strong superlatives without specific mention of overtones, mentioning only “appealing tonal qualities.”

“Appealing tonal qualities make the Deagan Marimba one of the most popular instruments. Its widespread use in every field of musical endeavor is convincing proof of its appeal. The lower register is surpassingly rich and mellow. . . . Bars are of finest Nagaed wood, post mounted, on beautiful Walnut finished frames.”

Photo 95

Both Leedy and Deagan had already incorporated electric tuning devices into their rosewood tuning operations prior to the advent of overtone tuning. Each company used a combination of hands-on listening assessment for rough tuning, followed by electric tuning aids to fine tune the bars. After rosewood blanks had dried sufficiently, preliminary tuning, drilling cord suspension holes, and final tuning took place. Leedy tuned rosewood bars a total of four times: three by ear, then the fourth and final time by electrical instrument calibration. [Photo 96] Leedy’s chief tuning engineer, Charles Hultsch, is shown carrying out the third tuning of marimba bars. [Photo 97]

“It is here that the bars receive their third tuning, there being four altogether; the fourth tuning is done in soundproof rooms where several scientific devices are employed. Leedy does not use the tuning-by-ear method.”

Photo 96

Photo 97

Photo 98

Photo 99

Six metallophones visible in the Leedy shop do not appear to be for retail, but rather, preliminary tuning by ear. Leedy’s statement disclaiming tuning by ear, therefore, seems to refer only to the final tuning. Along the left edge of this scene, a Deagan xylophone sits; an indication that the Leedy organization studied its competition in detail. Deagan also used metallophones for listening comparison when performing rough tuning rosewood bars. [Photo 98] Deagan tuner, Paul Fialkowski, used a metallophone to tune rosewood bars by ear. Fialkowski had perfect pitch to a degree of accuracy of one cent. [Photo 99] He also used emery powder to locate the nodal points for drilling bars for cord support holes. This process involves spreading the powder over the surface of the bar, then striking the bar with a mallet to produce vibrations, which causes the emery to coalesce over dead nodes.

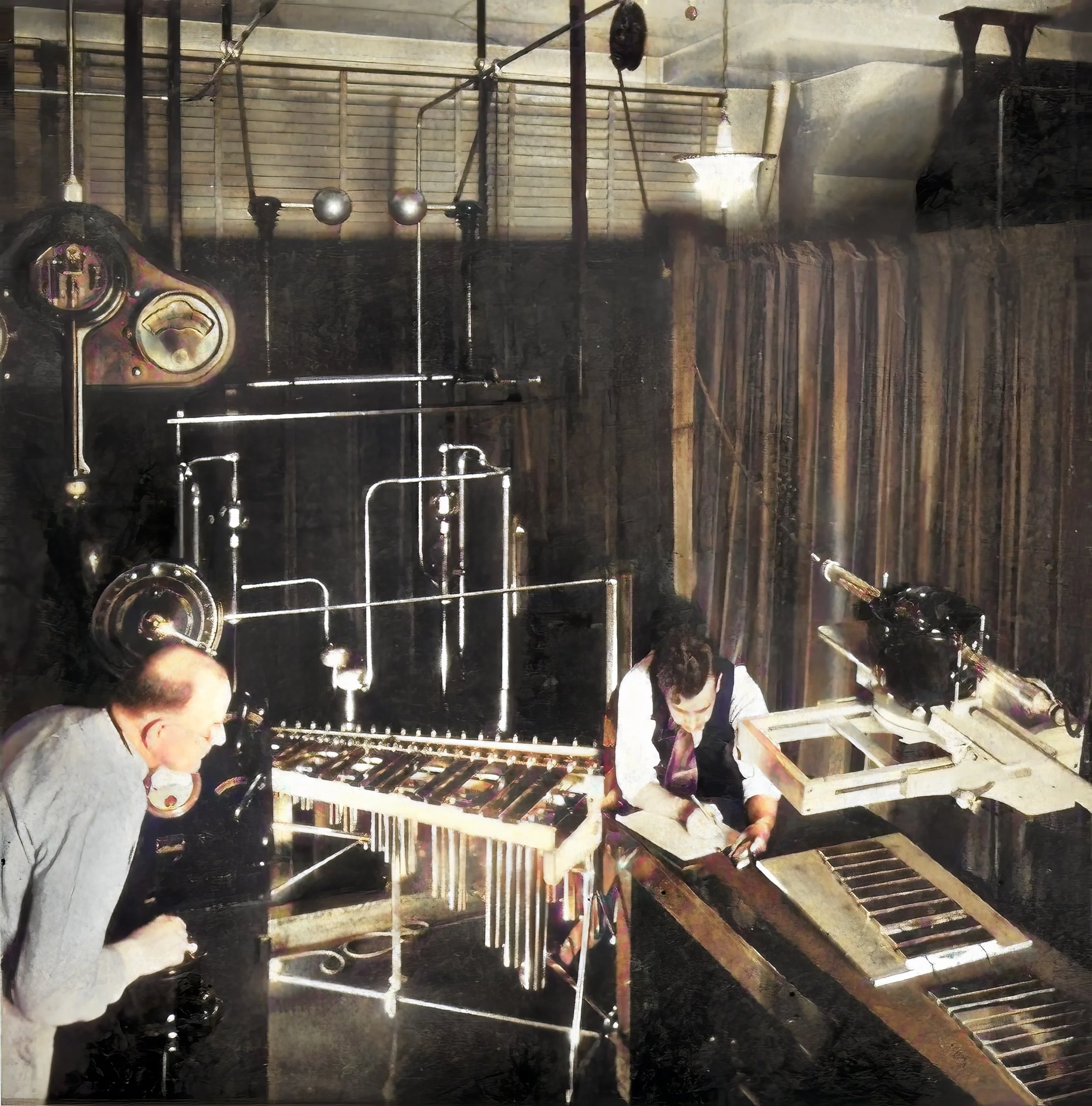

While Leedy was rather guarded about the precise nature of tuning devices used, and their application, Deagan openly propagated much of their technology. [Photo 100] A Deagan testing room shows scientific acoustics instruments. Two devices used by Deagan for intonation analysis were the Dea-Gan-Ometer for determining pitch to an accuracy of one cent, from A = 435 to A = 440, [Photo 101] and an oscillograph for providing visual display of sound waves. [Photo 102]

“Skilled sound experts and trained acoustical engineers with the facilities of the finest Laboratories known to modern science are back of the products that so proudly bear the DEAGAN trademark.”

“Deagan Laboratory Tuning Devices including the precision Dea-Gan-Ometer are accepted as perfect standards of pitch frequencies the world over. Complete analysis of the wave form and the beat frequencies are recorded on the oscillograph.”

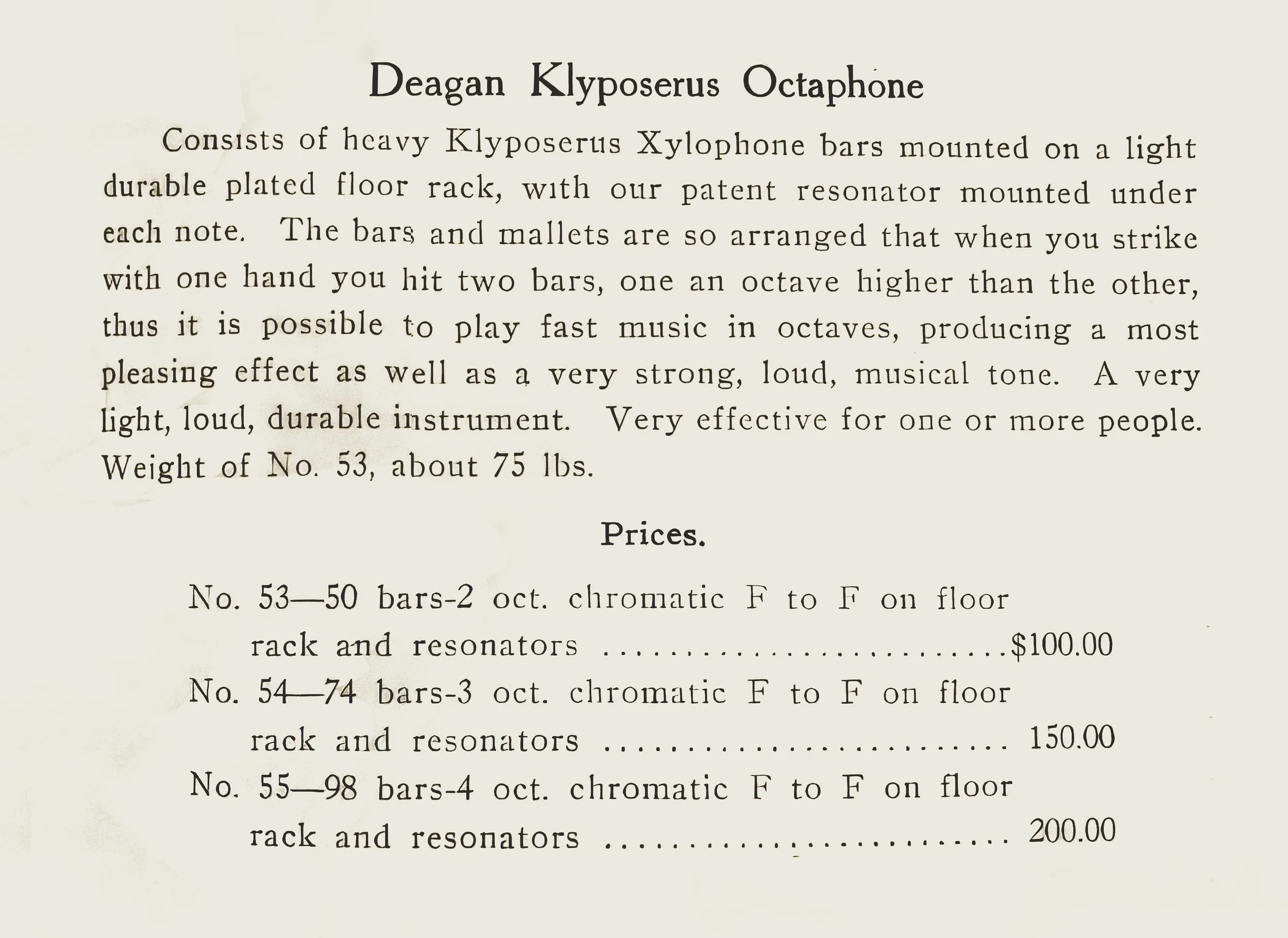

Photo 101

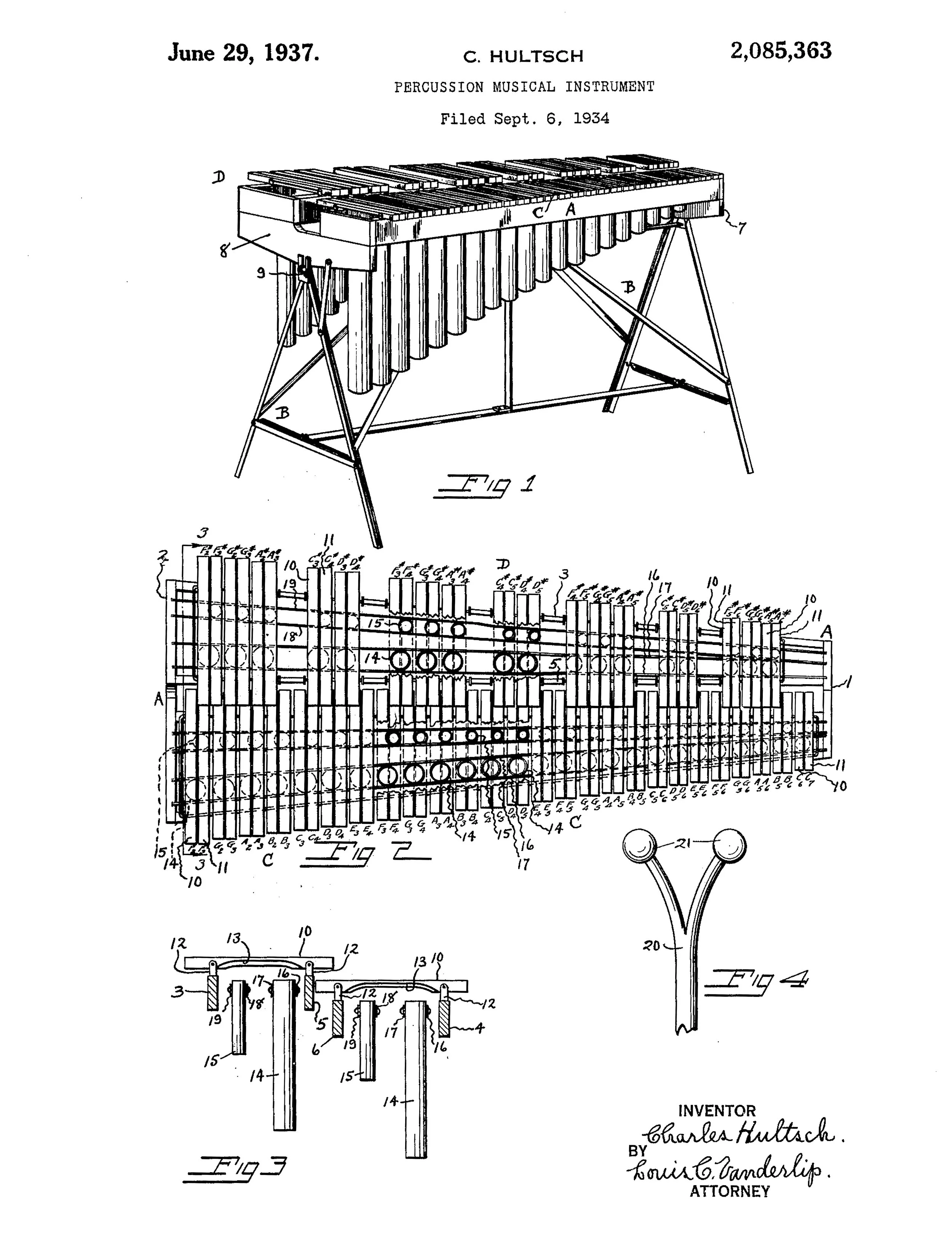

[Photos 103 - 107] On September 6, 1934, Leedy engineer Charles Hutsch filed application 742,894 with the US patent office for a highly unusual rosewood keyboard innovation. This design involved two bars arranged side-by-side for each note, with the bars voiced one octave apart. The invention included double headed mallets that enabled one to strike both bars simultaneously, thereby sounding an octave with each stroke. The aim of this instrument was to combine the resonant tone of the marimba with the bright tone of the xylophone in this unique timbre. This concept had previously been developed as a xylophone novelty by the Deagan company during the 1910s. It was called “Octaphone,” and was available then only by special order, with very little interest.

US Patent 2,085,363 was issued for Hultsch’s instrument on June 27, 1937, and assigned by him to C. G. Conn, Ltd of Elkhart, Indiana, which was by this time owner of the Leedy brand. The Leedy company named this new instrument “Octarimba,” combining the term “octave” with “marimba.” Leedy added this marimba to its Solo-Tone line as model number 5602, beginning production in 1934, as soon as the patent had been applied for. This marimba appeared to have a playing range of 3.0 octaves, with a low C3. However, because each note included an octave interval, the sounding range was 4.0 octaves.

[Photos 108 & 109] The rosewood bars of the octarimba were half the width of typical Leedy marimba bars, with each octave pair separated only by a thin felt spacer, to keep the bars close together for striking. Each pair of rosewood bars were the same length, but tuned an octave apart by controlling the tuning arches of each bar: the lower pitched bar had a longer arch compared to the higher pitched bar. Each rosewood bar had an individual aluminum resonator tuned to the corresponding pitch. [Photo 110] Leedy advertised the octarimba not as a novelty, but a legitimate rosewood keyboard:

“The recently introduced amazing, new, and exclusive Leedy instrument is the only musically correct Marimba-Xylophone ever made because the full, resonant speaking voice of the marimba is actually combined with the higher and more brilliant playing timbre of the xylophone in the same playing octave on one instrument.”

“Never before has there been a wood-bar instrument equal to the Octarimba’s eloquence, sympathetic response or latitude of expression! . . . Bars of genuine Honduras Rosewood tuned by the exclusive Leedv patented process which eliminates all discordant overtones . . ”

Photo 110

Photo 108

Photo 109

Photo 111

Photo 112

Notable musicians who performed professionally on the octarimba included Joe Green in the United States [Photo 111], Rudy Starita in England, and Richard Stangerup in Denmark. Despite the octarimba’s sonorous tone, however, two technical issues derailed its broad acceptance, both of which concerned the octarimba mallets rather than the instrument itself. [Photo 112] The double headed mallets were roughly twice as heavy as regular mallets, slowing down technique. Furthermore, in order for the two mallet balls to strike adjacent rosewood bars in the centers of both bars, the handle of the mallet had to be positioned exactly parallel to the bars. Any slight angling of the shaft, which is a necessary and common aspect of marimba technique, would cause one or both balls to miss the bar center, resulting in lack of tone. Consequently, octarimba sales were limited, resulting in the Leedy company manufacturing very few of these exotic rosewood keyboards.

[Photo 113] The Leedy Indianapolis factory finishing area includes a drying rack with freshly polished rosewood marimba bars air drying, as well as some raw bars on the rack above, awaiting finishing. From the inception of the American industrialized rosewood mallet percussion industry, shellac was used for sealing rosewood bars. Shellac is a resin secreted by the lac bug, which feeds on tree sap. This is not unlike bees feeding on pollen, and then secreting honey. Wood is a forest product, and shellac is a non-toxic forest byproduct, and therefore shellac pairs very well with wood surfaces. The time honored art of hand polishing fine woods with shellac produces stunningly beautiful finishes, exhibiting a soft glow that is neither matte not glossy. Due to shellac finishes, rosewood bars of 1900 - 1956 were not only the best quality wood, but were the most beautiful.

Photo 113

The period from the 1880s - 1920s saw the dissemination of nitrocellulose lacquer for both metal and wood finishing, though both Deagan and Leedy continued using shellac through the early 1940s. Nitrocellulose lacquer was eventually replaced by synthetic polymer lacquers, which are essentially plastic. The ease of use and durability of synthetic lacquer lead to the replacement of shellac industry wide in the second half of the 20th century. Interestingly, violin makers still use traditional varnish compounds based on 18th century formulas, and fine vintage furniture continues to be retouched and polished with shellac. Unlike mallet percussion, these artisan crafts never adopted synthetic finishing compounds.

Photo 114

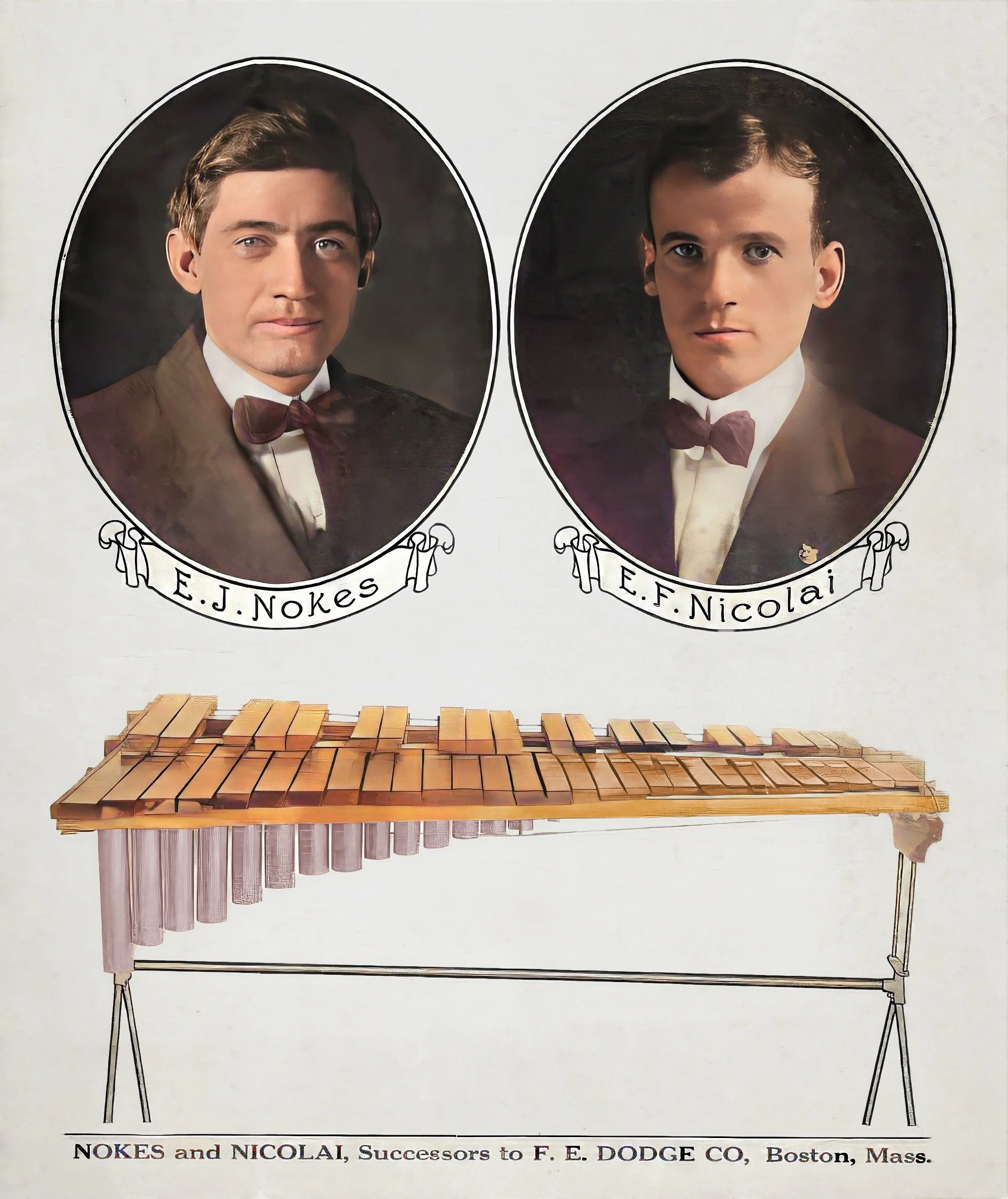

Though Deagan and Leedy dominated the rosewood percussion industry during its early period, there were smaller independent manufacturers in the United States at that time as well. These included E. R. Street of Hartford, Connecticut (1885 - c1930;) Nokes and Nicolai in Boston, Massachusetts (1912 - 1926,) and the Kohler-Liebich Company, Inc, based in Chicago, Illinois (1915-1940.) These companies all used Honduras rosewood bars from as early as the 1910s onward, for various models of xylophones and marimbas. [Photos 114 & 115] Nokes and Nicolai produced a concert xylophone, in ranges of 3.0 and 4.0 octaves, and also tabletop pit xylophones. Their catalog stated:

“These Xylophones are made of well seasoned, straight grained, live Honduras Rosewood, having a very brilliant and powerful tone.”

Photo 115

[Photos 116 & 117] By 1921, Kohler-Liebich offered a 3.5 octave marimba comparable to Leedy and Deagan instruments of that period. [Photos 118 & 119] E. R. Street made a wide bar Artist Model xylophone. He also produced marimbas with buzz resonators in the Central America style, or the American type without buzzers. [Photo 120] Street even designed a massive 5.5 octave marimba, ranging from low F2 to C8.

Photo 120

There was another independent company, which was highly influential: Musser Marimbas, Inc., established by Clair Musser in 1948. [Photos 121 & 122] From 1930 to about 1947, Clair Musser served as manager of the mallet instrument division of J. C. Deagan, Inc. He left the Deagan organization to form his own company in Chicago, right down the street from the Deagan building, only a few blocks away. Musser’s new factory included 10,000 square feet of floor space, and boasted:

“ . . the latest in scientific facilities embodying modern machinery and advanced production methods . . .The Grand Central Terminal of the Marimba and Vibe fraternity – the Mecca where the country’s leading dealers and the world’s most famous artists meet.”

“Musser Marimba Bars are made from the finest Rosewood grown on the mountains in Honduras, and kiln dried to less than 5% moisture. They are perfectly tuned by a master tuner in a special temperature controlled room of 72° Fahrenheit. This guarantees a balanced scale throughout at all times.”

Photo 122

Photo 121

This mention of kiln drying may indicate that, because Musser Marimbas was a new operation, there had been no time to slow age rosewood in open air, as had been standard industry practice. The rosewood used by Musser’s company certainly was superior grade, though, as Musser’s prior experience at Deagan had given him familiarity in sourcing premium Honduras rosewood. The master tuner referred to was Paul Fialkowski, who previously held that position at the Deagan plant, but followed Musser when he left to form his own company.

Photo 123

Photo 124

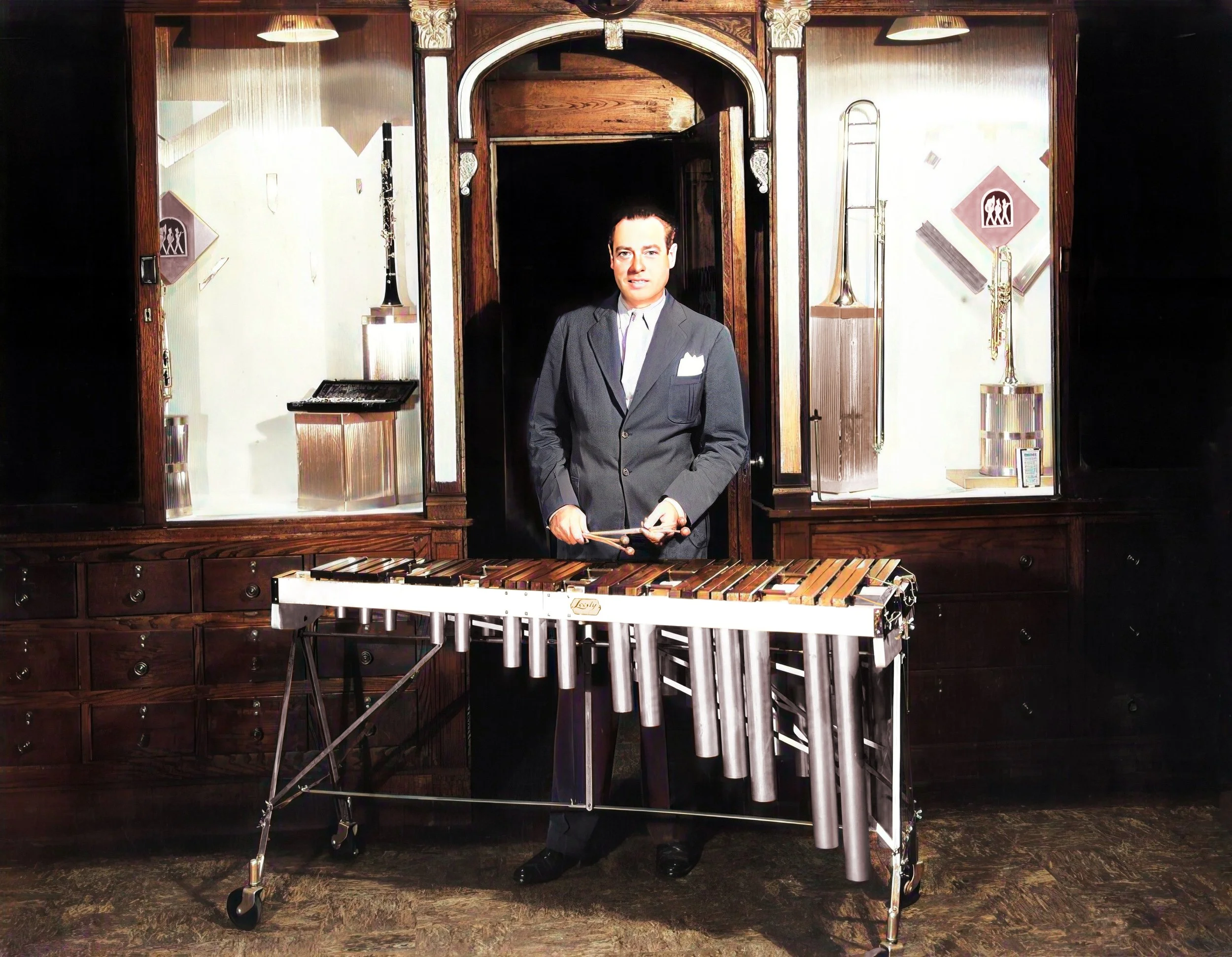

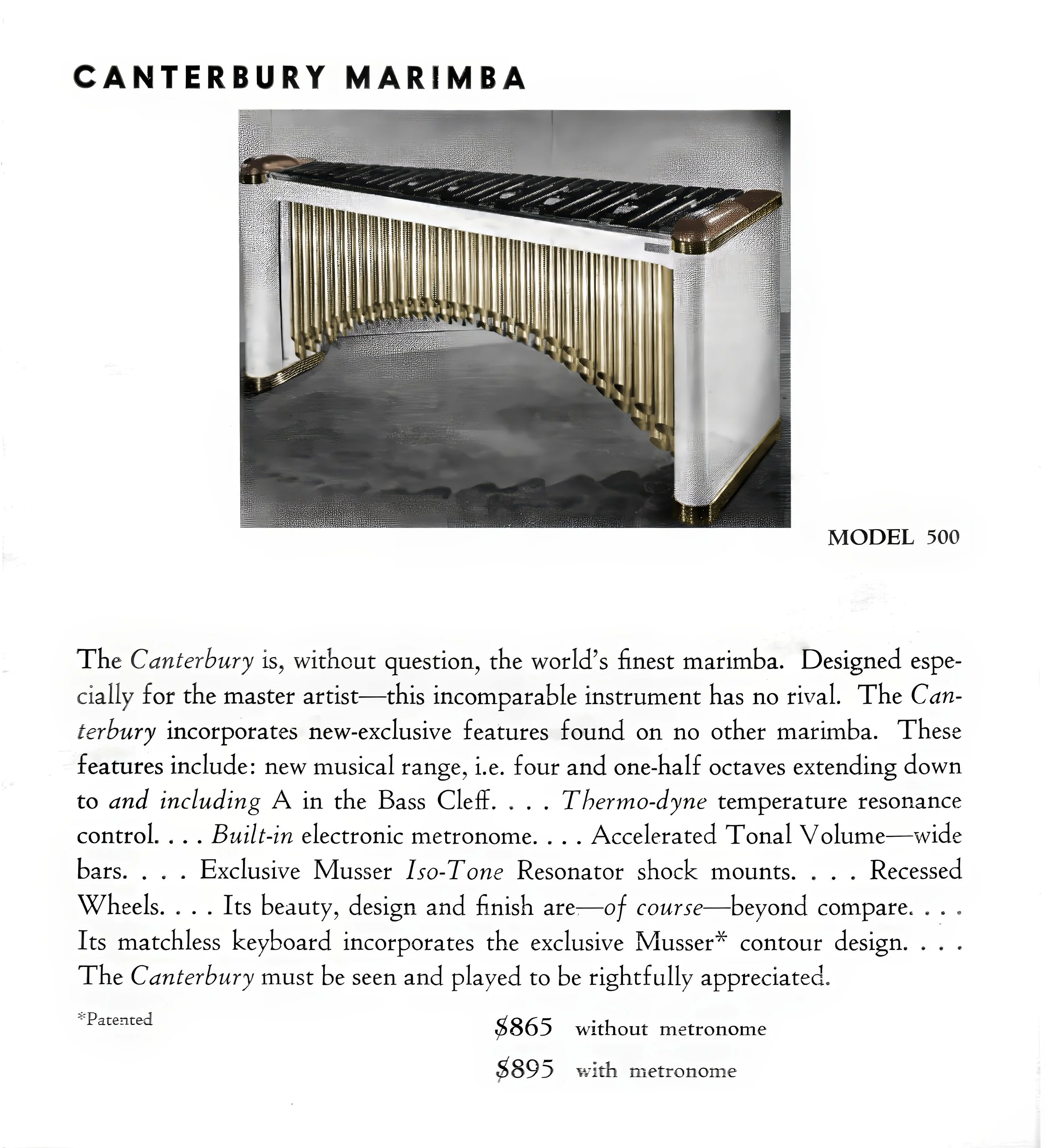

With the success of Musser Marimbas, there were now three major producers of premium quality rosewood keyboards in the United States: Deagan, Leedy, and Musser. As mentioned in company publicity, the Musser catalog under Clair Musser’s ownership included marimbas and vibraphones, but no xylophones or glockenspiels. Musser marimba models were well designed, sonorous, and of professional tier quality analogous to the topline Deagan and Leedy keyboards, to which consumers had become accustomed. [Photos 123 & 124] The Musser Canterbury marimba model #500, with a 4.3 octave range from A3 to C7, was the premier marimba in the Musser line; the crown jewel of Musser Marimbas, Inc.

“The Canterbury is, without question the world’s finest marimba. Designed especially for the master artist — this incomparable instrument has no rival. The Canterbury incorporates new-exclusive features found on no other marimba. Its beauty, design and finish are - of course - beyond compare. Its matchless keyboard incorporates the exclusive Musser contour design. The Canterbury must be seen and played to be rightfully appreciated.”

The contour bar design referred to marimba bars in the chromatic register having beveled edges at each end, creating rounded contours along the top and bottom surfaces. [Photos 125 & 126] This feature was designed and patented by Musser, through US patent application No. 140,554 filed on July 28, 1947. US Patent 160,108 was issued for this design on September 12, 1950. [Photos 127 & 128] Other Musser marimbas also incorporated beveled chromatic bar ends, including the 4.0 octave Century #100, and the 4.0 octave Windsor #30.

In 1956, after only eight years in business, Clair Musser sold Musser Marimbas, Inc. to the Lyons Band Instrument Company. Musser then retired from music, embarking on a new career in the scientific field, focusing on astronomy. The Musser brand was assimilated as a small component of the Lyons product line, thereby reducing focus on mallet percussion. Meanwhile, in 1954, Ella Deagan stepped down as president of J. C. Deagan, Inc., a position she had held for 30 years beginning in 1924. Absent Ella Deagan and Clair Musser, the focus at Deagan was no longer on rosewood keyboards, but rather, the tower carillon division, vibraphones, chimes, and organ percussions. Marimba and xylophone manufacturing at Deagan slowed to a very low ebb. In 1955, the Conn company sold its Leedy division to Slingerland, thereby ending the Leedy brand. Therefore, in the brief span from 1954 to 1956, the three principal organizations that had spearheaded the development of rosewood bar percussion, relinquished their roles in that field. By 1956, the glory days of premium rosewood had come to an end. The exciting, creative, and competitive era of the birth of the modern marimba and xylophone was over.

[Photos 129 - 148] This formative chapter in marimba and xylophone history left its indelible mark, which are the instruments themselves. The Honduras rosewood keyboards in these images represent the finest materials, design, and craftmanship that human ingenuity could create. A long and elaborate chain of events produced these magnificent instruments. Embodied in them are volcanic explosions in Central America long ago; trees that grew for decades in the sweltering sun and wetlands soil; human sweat that felled those tress, and oxen sweat that culled them from the forests; the shipping of logs across the globe; patient aging and precise cutting; refined tuning and beautiful polish; and rosewood echoes of lyrical music from a bygone era.